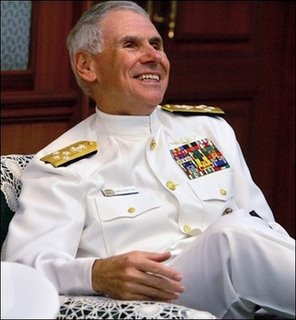

The United States and Vietnam have pledged to gradually deepen defence ties, with plans to conduct joint search and rescue exercises, Admiral William Fallon, the visiting commander of US forces in the Pacific, says(AFP/Pool/File/Elizabeth Dalziel)

The United States and Vietnam have pledged to gradually deepen defence ties, with plans to conduct joint search and rescue exercises, Admiral William Fallon, the visiting commander of US forces in the Pacific, says(AFP/Pool/File/Elizabeth Dalziel)Jul 21, 2006

By Sergei Blagov

Asia Times (Hong Kong)

MOSCOW - Former war adversaries and now growing trade partners, the US and Vietnam, are slowly but surely engaging in a strategic relationship that if fully consummated will have significant implications for Asia's regional balance of power, particularly toward counterbalancing China's growing military might in the region.

In an unprecedented gesture toward Vietnam's Communist Party-led government, Admiral William Fallon, head of the US Pacific Command, traveled to Vietnam in mid-July to discuss the possibility of conducting joint military maneuvers and also urged his Vietnamese counterpart, Defense Minister Colonel Phung Quang Thanh, to allow for more US naval visits to Vietnamese ports.

Fallon also suggested that the two countries' navies conduct future joint search-and-rescue exercises at sea. Thanh did not offer an immediate reply and impressed upon the senior US military official that he was reluctant to cause any misunderstanding with regional neighbors - presumably China - yet he promised to pass the proposal along to top Communist Party officials.

US-Vietnam military-to-military exchanges have quietly and rapidly intensified in recent years. On July 4, two US naval ships, the USS Patriot and USS Salvor, called on Vietnamese ports, the fourth such US naval visit to Vietnam since 2003. In the wake of the December 2004 tsunami in Southeast Asia, Hanoi allowed US military cargo planes unlimited flyover rights to assist in conducting rescue and supply missions.

The two sides now cooperate closely with the United States' counter-terrorism campaign, counter-narcotics operations and military medical-training programs. Hanoi recently agreed to exchanges under the Pentagon's international military education and training program, and its senior and middle-ranking military officials now participate in professional development programs with US allies in the region. The US and Vietnam also conduct an annual defense dialogue among mid-level military officers, which will hold its third session this year.

Early last month, US Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld visited Vietnam for talks aimed specifically at boosting bilateral security ties, and both countries agreed at those meetings to increase "exchanges at all levels of the military and in various ways to further strengthen the military-to-military relationship". As part of that agreement, two Vietnamese officers are now studying English in the US.

Rumsfeld said after his visit that "we have no plans for access to military facilities in Vietnam", a diplomatic statement made clearly to allay China's concerns about the budding US-Vietnam military relationship along its southern border. The United States is widely believed to want access to a major Vietnamese air terminal and a deepwater port, with the former US military facility at Cam Ranh Bay the most obvious option.

Strategic calculus

China's growing military might in the region is drawing the US and Vietnam closer together. Engaging Vietnam is an important part of Washington's greater strategic realignment in Asia, which has historically relied heavily on military bases in South Korea and Japan to maintain a strategic balance of power favorable to US interests.

With the United States' significant military commitments to Afghanistan and Iraq, the Pentagon has in recent years announced plans to redeploy some of its force commitments in Asia to the island of Guam. The United States' massive military presence in South Korea and Tokyo has at times stressed bilateral relations, and since the US lost access to military facilities in the Philippines in 1991-92, the Pentagon has sought to establish a new military footprint in Southeast Asia.

A sizable US presence at Vietnam's Cam Ranh Bay would profoundly alter Asia's strategic calculus. China's acquisition of anti-ship missiles and its buildup of ballistic missiles overtly aimed toward Taiwan also present a grave threat to US bases in the region. To counterbalance China's growing military capabilities, particularly its aggressive stance toward Taiwan, the US will require a joint force dependent on both naval and air power. A US presence at Cam Ranh Bay would also allow the US Navy to pressure China's fuel shipments in a future conflict, security analysts say.

Vietnam obviously harbors suspicions about China's regional intentions. The two countries fought a brief but brutal border war in 1979, and the two historical antagonists supported opposite sides in Cambodia's civil war throughout the 1980s and into the 1990s.

Notwithstanding, US access to Cam Ranh Bay is not a done deal. Hanoi has so far been extremely careful not to pique Beijing through its engagement with the US. Recent critical statements by Rumsfeld and US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice have called on Beijing to "demystify" its military spending and clarify its strategic intentions for the region, which have annoyed Chinese leaders. That will make it trickier for Hanoi to convince Beijing that its rapprochement with the US is not actually aimed at strategically containing China.

The strategic relationship is being promoted through vigorous, high-profile diplomacy. This year many top US officials have held or plan to hold high-level meetings with their Vietnamese counterparts, including US House Speaker Dennis Hastert, Rumsfeld, Rice, and President George W Bush. The US president is due to visit Vietnam while attending the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) leaders' meeting to be held in November in Hanoi.

Last week, Hanoi said Rice's visit to Vietnam late this month would boost "mutual understanding and cooperative relations" between the two countries.

"The continued exchange of delegations between Vietnam and the United States, including Rice's trip, will help promote mutual understanding and stable, long-term and win-win relations between the two countries," the Vietnamese Foreign Ministry said.

On July 12, Hanoi publicly marked the 11th anniversary of its normalization of diplomatic relations with the US, which has gradually evolved from cooperation in locating the remains of missing-in-action US soldiers to recent full-blown bilateral trade agreements. Last year, then-prime minister Phan Van Khai met with Bush in Washington and pledged to raise bilateral security relations to "a new level".

The more recent bilateral trade agreement, signed last month, will pave the way for Vietnam's accession to the World Trade Organization this year. The last remaining hurdle to full-blown normal relations is the ongoing debate inside the US Congress over whether to approve permanent normal trade relations (PNTR) with Vietnam. Some US Congress members have expressed reservations about Vietnam's human-rights record, particularly in relation to religious freedoms.

The Foreign Ministry has said PNTR is the final, important step for complete normal bilateral relations, which presumably will allow the two sides' emerging multi-level strategic relationship to evolve further, including possible joint military maneuvers.

US fills Russia's gap

The US is quickly moving to fill the gap left behind by Russia, until recently Vietnam's most important strategic ally. Throughout the Cold War, Moscow provided Hanoi with generous dollops of military and economic aid. Tens of thousands of Vietnamese, including senior military officers, studied in the Soviet Union and many still speak fluent Russian.

Russia has supplied Vietnam's army with most of its military hardware, and Moscow's armaments sales to Hanoi still amount to roughly a third of the two countries' trade. At the same time, military-to-military contacts have not developed in recent years. And Russia's joint war games with China last August sent a clear message to Vietnam that it needs to look elsewhere for future strategic assurances.

With the disintegration of the Soviet Union, economic relations were badly strained over the massive debts Hanoi owed Moscow. Against that backdrop, economic ties have sagged over a period that bilateral US and Vietnam trade has grown exponentially. In July 2002, Russia rushed to withdraw its military presence at Vietnam's Cam Ranh Bay, even though Moscow still had two more years on its 25-year contract to use the naval facilities for free.

Officially, the Kremlin explained its Cam Ranh Bay closure as a cost-cutting measure, but many strategic analysts saw the move as an attempt to appease and please China as a new strategic partner. After the Russian withdrawal, Hanoi originally indicated new plans to turn Cam Ranh Bay into a sort of economic hub, similar to what the Philippines has attempted with its Subic Bay facilities. Provincial authorities now plan a number of projects, including a cement factory in Cam Thinh Dong, shipyards in Cam Phu and Cam Phuc Nam, industrial zones in Nam Cam Ranh and Bac Cam Ranh, and tourism areas for Bai Dai and Cam Lap.

Vietnamese authorities are also mulling other projects, including upgrading Cam Ranh Bay's airport into an international gateway and rebuilding Ba Ngoi seaport into a container terminal. These plans would appear to indicate Hanoi's intention to scale down the military and build up the economic uses of Cam Ranh Bay's facilities. But if the US pushes for military access, and China doesn't openly demur, there are growing indications Vietnam would warmly entertain any and all US proposals.

Sergei Blagov covers Russia and post-Soviet states, with special attention to Asia-related issues. He has contributed to Asia Times Online since 1996 and was based in Southeast Asia from 1983 to 1997. Nova Science Publishers, New York, has published two of his books on Vietnamese history.

In an unprecedented gesture toward Vietnam's Communist Party-led government, Admiral William Fallon, head of the US Pacific Command, traveled to Vietnam in mid-July to discuss the possibility of conducting joint military maneuvers and also urged his Vietnamese counterpart, Defense Minister Colonel Phung Quang Thanh, to allow for more US naval visits to Vietnamese ports.

Fallon also suggested that the two countries' navies conduct future joint search-and-rescue exercises at sea. Thanh did not offer an immediate reply and impressed upon the senior US military official that he was reluctant to cause any misunderstanding with regional neighbors - presumably China - yet he promised to pass the proposal along to top Communist Party officials.

US-Vietnam military-to-military exchanges have quietly and rapidly intensified in recent years. On July 4, two US naval ships, the USS Patriot and USS Salvor, called on Vietnamese ports, the fourth such US naval visit to Vietnam since 2003. In the wake of the December 2004 tsunami in Southeast Asia, Hanoi allowed US military cargo planes unlimited flyover rights to assist in conducting rescue and supply missions.

The two sides now cooperate closely with the United States' counter-terrorism campaign, counter-narcotics operations and military medical-training programs. Hanoi recently agreed to exchanges under the Pentagon's international military education and training program, and its senior and middle-ranking military officials now participate in professional development programs with US allies in the region. The US and Vietnam also conduct an annual defense dialogue among mid-level military officers, which will hold its third session this year.

Early last month, US Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld visited Vietnam for talks aimed specifically at boosting bilateral security ties, and both countries agreed at those meetings to increase "exchanges at all levels of the military and in various ways to further strengthen the military-to-military relationship". As part of that agreement, two Vietnamese officers are now studying English in the US.

Rumsfeld said after his visit that "we have no plans for access to military facilities in Vietnam", a diplomatic statement made clearly to allay China's concerns about the budding US-Vietnam military relationship along its southern border. The United States is widely believed to want access to a major Vietnamese air terminal and a deepwater port, with the former US military facility at Cam Ranh Bay the most obvious option.

Strategic calculus

China's growing military might in the region is drawing the US and Vietnam closer together. Engaging Vietnam is an important part of Washington's greater strategic realignment in Asia, which has historically relied heavily on military bases in South Korea and Japan to maintain a strategic balance of power favorable to US interests.

With the United States' significant military commitments to Afghanistan and Iraq, the Pentagon has in recent years announced plans to redeploy some of its force commitments in Asia to the island of Guam. The United States' massive military presence in South Korea and Tokyo has at times stressed bilateral relations, and since the US lost access to military facilities in the Philippines in 1991-92, the Pentagon has sought to establish a new military footprint in Southeast Asia.

A sizable US presence at Vietnam's Cam Ranh Bay would profoundly alter Asia's strategic calculus. China's acquisition of anti-ship missiles and its buildup of ballistic missiles overtly aimed toward Taiwan also present a grave threat to US bases in the region. To counterbalance China's growing military capabilities, particularly its aggressive stance toward Taiwan, the US will require a joint force dependent on both naval and air power. A US presence at Cam Ranh Bay would also allow the US Navy to pressure China's fuel shipments in a future conflict, security analysts say.

Vietnam obviously harbors suspicions about China's regional intentions. The two countries fought a brief but brutal border war in 1979, and the two historical antagonists supported opposite sides in Cambodia's civil war throughout the 1980s and into the 1990s.

Notwithstanding, US access to Cam Ranh Bay is not a done deal. Hanoi has so far been extremely careful not to pique Beijing through its engagement with the US. Recent critical statements by Rumsfeld and US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice have called on Beijing to "demystify" its military spending and clarify its strategic intentions for the region, which have annoyed Chinese leaders. That will make it trickier for Hanoi to convince Beijing that its rapprochement with the US is not actually aimed at strategically containing China.

The strategic relationship is being promoted through vigorous, high-profile diplomacy. This year many top US officials have held or plan to hold high-level meetings with their Vietnamese counterparts, including US House Speaker Dennis Hastert, Rumsfeld, Rice, and President George W Bush. The US president is due to visit Vietnam while attending the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) leaders' meeting to be held in November in Hanoi.

Last week, Hanoi said Rice's visit to Vietnam late this month would boost "mutual understanding and cooperative relations" between the two countries.

"The continued exchange of delegations between Vietnam and the United States, including Rice's trip, will help promote mutual understanding and stable, long-term and win-win relations between the two countries," the Vietnamese Foreign Ministry said.

On July 12, Hanoi publicly marked the 11th anniversary of its normalization of diplomatic relations with the US, which has gradually evolved from cooperation in locating the remains of missing-in-action US soldiers to recent full-blown bilateral trade agreements. Last year, then-prime minister Phan Van Khai met with Bush in Washington and pledged to raise bilateral security relations to "a new level".

The more recent bilateral trade agreement, signed last month, will pave the way for Vietnam's accession to the World Trade Organization this year. The last remaining hurdle to full-blown normal relations is the ongoing debate inside the US Congress over whether to approve permanent normal trade relations (PNTR) with Vietnam. Some US Congress members have expressed reservations about Vietnam's human-rights record, particularly in relation to religious freedoms.

The Foreign Ministry has said PNTR is the final, important step for complete normal bilateral relations, which presumably will allow the two sides' emerging multi-level strategic relationship to evolve further, including possible joint military maneuvers.

US fills Russia's gap

The US is quickly moving to fill the gap left behind by Russia, until recently Vietnam's most important strategic ally. Throughout the Cold War, Moscow provided Hanoi with generous dollops of military and economic aid. Tens of thousands of Vietnamese, including senior military officers, studied in the Soviet Union and many still speak fluent Russian.

Russia has supplied Vietnam's army with most of its military hardware, and Moscow's armaments sales to Hanoi still amount to roughly a third of the two countries' trade. At the same time, military-to-military contacts have not developed in recent years. And Russia's joint war games with China last August sent a clear message to Vietnam that it needs to look elsewhere for future strategic assurances.

With the disintegration of the Soviet Union, economic relations were badly strained over the massive debts Hanoi owed Moscow. Against that backdrop, economic ties have sagged over a period that bilateral US and Vietnam trade has grown exponentially. In July 2002, Russia rushed to withdraw its military presence at Vietnam's Cam Ranh Bay, even though Moscow still had two more years on its 25-year contract to use the naval facilities for free.

Officially, the Kremlin explained its Cam Ranh Bay closure as a cost-cutting measure, but many strategic analysts saw the move as an attempt to appease and please China as a new strategic partner. After the Russian withdrawal, Hanoi originally indicated new plans to turn Cam Ranh Bay into a sort of economic hub, similar to what the Philippines has attempted with its Subic Bay facilities. Provincial authorities now plan a number of projects, including a cement factory in Cam Thinh Dong, shipyards in Cam Phu and Cam Phuc Nam, industrial zones in Nam Cam Ranh and Bac Cam Ranh, and tourism areas for Bai Dai and Cam Lap.

Vietnamese authorities are also mulling other projects, including upgrading Cam Ranh Bay's airport into an international gateway and rebuilding Ba Ngoi seaport into a container terminal. These plans would appear to indicate Hanoi's intention to scale down the military and build up the economic uses of Cam Ranh Bay's facilities. But if the US pushes for military access, and China doesn't openly demur, there are growing indications Vietnam would warmly entertain any and all US proposals.

Sergei Blagov covers Russia and post-Soviet states, with special attention to Asia-related issues. He has contributed to Asia Times Online since 1996 and was based in Southeast Asia from 1983 to 1997. Nova Science Publishers, New York, has published two of his books on Vietnamese history.

1 comment:

If American make Vietnam like Israel. Cambodia would be a Palestine... Another exodus of refugees to Thailand will soon come...Get out the country Cambodians before it is too late.

Post a Comment