Norodom Sihamoni, the king of Cambodia, presenting Jonathan Hollander of the Battery Dance Company with a gift. (Photo: Tang Chhin Sothy/Agence France-Presse, for The New York Times)

Norodom Sihamoni, the king of Cambodia, presenting Jonathan Hollander of the Battery Dance Company with a gift. (Photo: Tang Chhin Sothy/Agence France-Presse, for The New York Times)By ERIKA KINETZ

The New York Times

PHNOM PENH, Cambodia

THE rehearsal began with pliés. Well, sort of. For dancers throughout Europe and North America, the plié is the de rigueur start of the dancing day; if you don’t bend your legs — that is, plié — you simply cannot move. So it was only natural that Bafana Matea, one of six dancers from the Battery Dance Company of New York City rehearsing with 22 Cambodian dancers for a performance earlier this month, first called for pliés.

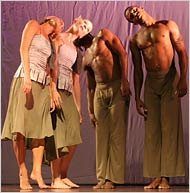

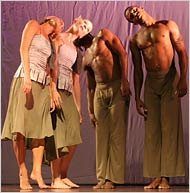

Dancers from the company performing in Phnom Penh on Oct. 21. (Photo: Tang Chhin Sothy/Agence France-Presse, for The New York Times)

Dancers from the company performing in Phnom Penh on Oct. 21. (Photo: Tang Chhin Sothy/Agence France-Presse, for The New York Times)

There was no response.

Fred Frumberg, the executive director of Amrita Performing Arts, the nonprofit group that was producing the show, quietly pulled Mr. Matea aside and said, “We don’t have any pliés here.” Ballet has come to Cambodia before, but neither it nor its vocabulary is part of these dancers’ tradition. So Mr. Matea, beaming, turned back to the assembled Khmer crowd and said, “O.K., we’re going to do some bending.”

This is the new face of cultural diplomacy. State Department financing for projects like this one — in which Battery Dance did a four-day workshop with local dancers, creating a collaborative work, “Homage to Cambodia” — has more than tripled since 2000. In late September, the first lady, Laura Bush, announced a new Global Cultural Initiative to export film, dance, theater, music, literature and art, and thus reach more deeply into other societies, especially Muslim ones.

“The world is again breaking into camps,” said Joseph Mussomeli, the United States ambassador to Cambodia. “There is an us-versus-them.” Cultural diplomacy, he added, “probably hasn’t been this important since the cold war.”

This summer, the United States Embassy in Beirut, Lebanon, once again made its presence felt on the cultural scene by sponsoring a photo exhibition, an experimental jazz performance, a classical music concert and a visit from the Whiffenpoofs, Yale University’s a cappella singers. Americans have been teaching hip-hop in Indonesia, Malaysia and Jordan. Chinese and American filmmakers are getting together to talk shop. Videography is coming to Belarus. And all of it is thanks to Uncle Sam.

So far, however, the budget for cultural diplomacy remains small: $5.1 million this year, a fraction of the $431 million allotted to the State Department’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs. (The bulk goes to exchange and educational programs like the Fulbright fellowships.) But it has been growing. In 2000, $1.5 million was allotted to cultural programs; for next year, the Bush administration has requested $7.4 million.

“There’s not a lot of money changing hands here,” said Michael Kaiser, the president of the Kennedy Center in Washington, one of the State Department’s partners in the Global Cultural Initiative. “This is not about financial support. This is about encouraging us and many others to take international exchange seriously.”

Today’s efforts pale in comparison to the cultural offensive of the cold war era, when there was a government office dedicated to recruiting American artists and sending them overseas. From 1955 to 1972, the New York City Ballet did six tours financed by the State Department, most famously performing in Moscow during the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, to enthusiastic crowds. Paul Taylor also received extensive support from the State Department in the 1960’s and 70’s that, Mr. Taylor wrote in an e-mail message, was “integral” to his company’s financial success. The State Department financed Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater’s first international tour in 1962, to Asia, and saved the company from bankruptcy more than once.

Financing was drastically cut in the 90’s. Ailey, which continues to tour extensively abroad, has not received State Department support since its 1985 tour of China. The New York City Ballet no longer receives State Department money, nor does the Taylor company. “If you compare it to other countries, what the U.S. State Department does is almost nothing,” Paul Szilard, a longtime dance producer, wrote in an e-mail message. CulturesFrance, which sponsors French artists and exhibitions abroad, has an annual budget of more than $37 million. Here in Cambodia, the French are a far more visible cultural presence than the Americans, perhaps in part because of past colonial ties. The French organize and finance numerous small events and spend $377,500 on four big festivals every year here. The United States Embassy, in contrast, has spent $29,000 on three events since December.

Today, individual artists receive direct State Department money at the request of American embassies abroad. “The days of Washington contacting us and asking us to tour, and supporting it, are long gone,” John Tomlinson, the Taylor company’s general manager, wrote in an e-mail message.

Like many contemporary choreographers, Jonathan Hollander, the artistic director of the Battery Dance Company, draws on a variety of styles, among them jazz, hip-hop, ballet and modern dance. He has been successful in getting money from the State Department in large part, he said, because he has learned to speak the language of diplomacy.

“I think a lot of other choreographers might have trouble communicating about their work,” Mr. Hollander said. “They don’t necessarily see their companies as agents of change and social action.”

Mr. Hollander began touring in Asia in the early 1990’s, when he was a Fulbright lecturer in India, talking about dance and touring with his company. But he did not get his big break with the State Department until 2004, when it paid for his company to tour North Africa. “That was the first time I didn’t come home with my credit cards maxed out,” he said.

Mr. Hollander’s company stopped in Phnom Penh this month as part of a six-nation tour of Asia, for which the State Department is footing most of the $125,000 bill, before returning to New York for three performances at the TriBeCa Performing Arts Center on Nov. 15 and 16.

With money, of course, comes power. But, so far, the use of art as a strategic arm of the state doesn’t seem to bother too many people.

In Cambodia, dance has long been linked to the state, God and the king. Sophiline Shapiro, the Cambodian-born artistic director of the Khmer Arts Academy, which has a school in Long Beach, Calif., and a new dance company in Cambodia, was one of the first dance students at the School of Fine Arts in Phnom Penh after the fall of the Khmer Rouge in 1979. During the ensuing civil war, she and her fellow art students had to do military drills in the morning. In 1984, she was one of 40 people sent by the government to perform classical Khmer dance in the rice paddies of northeastern Cambodia. “They sent us there to make people see the greatness of the government,” she said. “At first I felt angry because it was a dangerous place.”

But after a show in one of the villages, she said, a peasant farmer asked her if she was a human being. “He said, ‘Do you eat rice like me?’ ” she recalled. “ ‘Do you go to the bathroom?’ ” The next morning, a vendor in the village market told her that Khmer Rouge guerrillas had gone to the show planning to blow up the stage, but ended up watching the dance instead.

Contemporary dance has no roots in Cambodia; a generation of artists was wiped out with the 1.7 million people who died in Cambodia during the Khmer Rouge years. Only after years of painstaking work to rescue and recover classical forms have some people started to turn their attention to innovation. American modern dance is nearly unheard of.

The 22 Cambodians working with Battery Dance had dedicated their youths to embodying the strict forms of classical Khmer dance. For most of them, Battery Dance was American dance. The sweeping improvisations the Battery dancers led them through — jumps and lifts and balletic ports de bras — left them sore, but hungry for more.

This new way of working, the dancers said, was wonderfully strange. There was the simple strangeness of scale; Western movements were bigger than what they were accustomed to. Then there were more complex oddities: having to open their legs in dance; sharing weight, men and women dancing together; and the biggest challenge of all, having to make their own decisions.

“Before, I used to eat something sweet, but now I feel there are people who add some more ingredients,” said Phon Sopheap, 26, who has studied classical Khmer dance for 15 years and teaches at the National School of Fine Arts.

Proeung Chhieng, the dean of choreographic arts at the Royal University of Fine Arts here, said he would like to introduce ballet and contemporary choreography into the curriculum. “We have to do everything,” he said. “Homage to Cambodia” was performed at Chaktomuk Conference Hall in Phnom Penh on Oct. 21, attended by the king. After the curtain closed, first one cheer and then another rose up from the stage. The dancers clumped together three and four deep, grinning hugely and holding great clumps of lilies, as friends and relatives took photos of them with the United States Ambassador.

“Before, we just follow the teacher,” said Belle Chumvansodha, 21, one of the Cambodian dancers. The dancers from New York, she said, “taught me to open my heart and open my mind and do something I want.”

Dancers from the company performing in Phnom Penh on Oct. 21. (Photo: Tang Chhin Sothy/Agence France-Presse, for The New York Times)

Dancers from the company performing in Phnom Penh on Oct. 21. (Photo: Tang Chhin Sothy/Agence France-Presse, for The New York Times)There was no response.

Fred Frumberg, the executive director of Amrita Performing Arts, the nonprofit group that was producing the show, quietly pulled Mr. Matea aside and said, “We don’t have any pliés here.” Ballet has come to Cambodia before, but neither it nor its vocabulary is part of these dancers’ tradition. So Mr. Matea, beaming, turned back to the assembled Khmer crowd and said, “O.K., we’re going to do some bending.”

This is the new face of cultural diplomacy. State Department financing for projects like this one — in which Battery Dance did a four-day workshop with local dancers, creating a collaborative work, “Homage to Cambodia” — has more than tripled since 2000. In late September, the first lady, Laura Bush, announced a new Global Cultural Initiative to export film, dance, theater, music, literature and art, and thus reach more deeply into other societies, especially Muslim ones.

“The world is again breaking into camps,” said Joseph Mussomeli, the United States ambassador to Cambodia. “There is an us-versus-them.” Cultural diplomacy, he added, “probably hasn’t been this important since the cold war.”

This summer, the United States Embassy in Beirut, Lebanon, once again made its presence felt on the cultural scene by sponsoring a photo exhibition, an experimental jazz performance, a classical music concert and a visit from the Whiffenpoofs, Yale University’s a cappella singers. Americans have been teaching hip-hop in Indonesia, Malaysia and Jordan. Chinese and American filmmakers are getting together to talk shop. Videography is coming to Belarus. And all of it is thanks to Uncle Sam.

So far, however, the budget for cultural diplomacy remains small: $5.1 million this year, a fraction of the $431 million allotted to the State Department’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs. (The bulk goes to exchange and educational programs like the Fulbright fellowships.) But it has been growing. In 2000, $1.5 million was allotted to cultural programs; for next year, the Bush administration has requested $7.4 million.

“There’s not a lot of money changing hands here,” said Michael Kaiser, the president of the Kennedy Center in Washington, one of the State Department’s partners in the Global Cultural Initiative. “This is not about financial support. This is about encouraging us and many others to take international exchange seriously.”

Today’s efforts pale in comparison to the cultural offensive of the cold war era, when there was a government office dedicated to recruiting American artists and sending them overseas. From 1955 to 1972, the New York City Ballet did six tours financed by the State Department, most famously performing in Moscow during the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, to enthusiastic crowds. Paul Taylor also received extensive support from the State Department in the 1960’s and 70’s that, Mr. Taylor wrote in an e-mail message, was “integral” to his company’s financial success. The State Department financed Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater’s first international tour in 1962, to Asia, and saved the company from bankruptcy more than once.

Financing was drastically cut in the 90’s. Ailey, which continues to tour extensively abroad, has not received State Department support since its 1985 tour of China. The New York City Ballet no longer receives State Department money, nor does the Taylor company. “If you compare it to other countries, what the U.S. State Department does is almost nothing,” Paul Szilard, a longtime dance producer, wrote in an e-mail message. CulturesFrance, which sponsors French artists and exhibitions abroad, has an annual budget of more than $37 million. Here in Cambodia, the French are a far more visible cultural presence than the Americans, perhaps in part because of past colonial ties. The French organize and finance numerous small events and spend $377,500 on four big festivals every year here. The United States Embassy, in contrast, has spent $29,000 on three events since December.

Today, individual artists receive direct State Department money at the request of American embassies abroad. “The days of Washington contacting us and asking us to tour, and supporting it, are long gone,” John Tomlinson, the Taylor company’s general manager, wrote in an e-mail message.

Like many contemporary choreographers, Jonathan Hollander, the artistic director of the Battery Dance Company, draws on a variety of styles, among them jazz, hip-hop, ballet and modern dance. He has been successful in getting money from the State Department in large part, he said, because he has learned to speak the language of diplomacy.

“I think a lot of other choreographers might have trouble communicating about their work,” Mr. Hollander said. “They don’t necessarily see their companies as agents of change and social action.”

Mr. Hollander began touring in Asia in the early 1990’s, when he was a Fulbright lecturer in India, talking about dance and touring with his company. But he did not get his big break with the State Department until 2004, when it paid for his company to tour North Africa. “That was the first time I didn’t come home with my credit cards maxed out,” he said.

Mr. Hollander’s company stopped in Phnom Penh this month as part of a six-nation tour of Asia, for which the State Department is footing most of the $125,000 bill, before returning to New York for three performances at the TriBeCa Performing Arts Center on Nov. 15 and 16.

With money, of course, comes power. But, so far, the use of art as a strategic arm of the state doesn’t seem to bother too many people.

In Cambodia, dance has long been linked to the state, God and the king. Sophiline Shapiro, the Cambodian-born artistic director of the Khmer Arts Academy, which has a school in Long Beach, Calif., and a new dance company in Cambodia, was one of the first dance students at the School of Fine Arts in Phnom Penh after the fall of the Khmer Rouge in 1979. During the ensuing civil war, she and her fellow art students had to do military drills in the morning. In 1984, she was one of 40 people sent by the government to perform classical Khmer dance in the rice paddies of northeastern Cambodia. “They sent us there to make people see the greatness of the government,” she said. “At first I felt angry because it was a dangerous place.”

But after a show in one of the villages, she said, a peasant farmer asked her if she was a human being. “He said, ‘Do you eat rice like me?’ ” she recalled. “ ‘Do you go to the bathroom?’ ” The next morning, a vendor in the village market told her that Khmer Rouge guerrillas had gone to the show planning to blow up the stage, but ended up watching the dance instead.

Contemporary dance has no roots in Cambodia; a generation of artists was wiped out with the 1.7 million people who died in Cambodia during the Khmer Rouge years. Only after years of painstaking work to rescue and recover classical forms have some people started to turn their attention to innovation. American modern dance is nearly unheard of.

The 22 Cambodians working with Battery Dance had dedicated their youths to embodying the strict forms of classical Khmer dance. For most of them, Battery Dance was American dance. The sweeping improvisations the Battery dancers led them through — jumps and lifts and balletic ports de bras — left them sore, but hungry for more.

This new way of working, the dancers said, was wonderfully strange. There was the simple strangeness of scale; Western movements were bigger than what they were accustomed to. Then there were more complex oddities: having to open their legs in dance; sharing weight, men and women dancing together; and the biggest challenge of all, having to make their own decisions.

“Before, I used to eat something sweet, but now I feel there are people who add some more ingredients,” said Phon Sopheap, 26, who has studied classical Khmer dance for 15 years and teaches at the National School of Fine Arts.

Proeung Chhieng, the dean of choreographic arts at the Royal University of Fine Arts here, said he would like to introduce ballet and contemporary choreography into the curriculum. “We have to do everything,” he said. “Homage to Cambodia” was performed at Chaktomuk Conference Hall in Phnom Penh on Oct. 21, attended by the king. After the curtain closed, first one cheer and then another rose up from the stage. The dancers clumped together three and four deep, grinning hugely and holding great clumps of lilies, as friends and relatives took photos of them with the United States Ambassador.

“Before, we just follow the teacher,” said Belle Chumvansodha, 21, one of the Cambodian dancers. The dancers from New York, she said, “taught me to open my heart and open my mind and do something I want.”

No comments:

Post a Comment