Human Rights Watch

Donors Should Not Let Government Ignore Commitments

(London, October 4, 2006) – Cambodia’s international donors must hold the country’s government to its commitments to protect human rights, fight corruption, and ensure the protection of land and natural resources, a group of five leading international organizations from Asia, Europe and the United States said in a statement today.

Ambassadors from donor countries – which provide half of Cambodia’s annual budget – are scheduled to meet in Phnom Penh on Thursday for a half-yearly review of the government’s progress in meeting reform targets set at their last meeting.

The statement, issued jointly by Human Rights Watch, Global Witness, FORUM-ASIA, the Asian Human Rights Commission, and the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), follows up on a letter the group sent to donors earlier this year, prior to their annual Consultative Group (CG) meeting in March.

“For more than a decade, the Cambodian government has taken donors for a ride by promising reforms but failing to deliver,” said Brad Adams, Asia director at Human Rights Watch. “It’s not the donors who are hurt by attacks on labor activists, a politicized judiciary and rampant corruption. It’s Cambodia’s poor and marginalized citizens who bear the brunt of bad governance and the failure of donors to insist on change.”

The five organizations renewed their call for donors to increase their assistance through nongovernmental channels to promote human rights, development, the rule of law, counter-corruption, and media freedom. Budgetary support and development assistance to the government should be contingent on:

“Pledges by the Cambodian government to reduce poverty are meaningless if rhetoric is not matched by action,” said Patrick Alley from Global Witness. “Donors should make it clear that continued assistance will depend on the Cambodian government keeping its promises. Otherwise, the whole exercise of setting benchmarks for reform is a sham.”

Cambodians continue to fall into poverty and landlessness because the government refuses to end bald-faced corruption by officials and reform a court system that is used to advance political agendas, silence critics, and strip people of their land. At the last meeting, donors insisted on the adoption of a strong anti-corruption law as the minimum that they expected from the government, but even this modest step – in the works since 1995 – has not taken place.

Since the March CG meeting, senior government officials have continued to issue illegal contracts enabling private companies to clear-cut the country’s forests under the guise of economic land concessions, damaging local people’s livelihoods and circumventing the moratorium on cutting in logging concessions. This is in violation of Cambodia’s Land Law and a recent sub-decree on economic land concessions, both of which were drafted with support from international donors.

Meanwhile, the government has yet to deliver on its repeated commitments to publicly disclose information on economic land concessions and cancel those that have been granted illegally. This lack of transparency further reduces the already minimal scope Cambodians have to hold officials to account.

“There’s a huge gap between reforms promised by the Cambodian government at each donor meeting and the ongoing hardships faced by Cambodian citizens every day,” said Anselmo Lee, executive director of FORUM-ASIA. “Donors must stop sending mixed messages to the Cambodian government by demanding reforms while increasing aid. This hypocrisy must end now.”

Government crackdowns on freedom of speech and public assembly – together with arrests and harassment of communities seeking to maintain their access to land and natural resources – has created a repressive atmosphere, prohibiting many citizens from airing their grievances in public.

Syndicates comprising relatives of senior officials and elite military units continue to conduct illegal logging operations with impunity in several provinces, notably Kompong Thom. A relative of the prime minister who shot at two community forestry activists in Tumring Commune last year after they attempted to stop his illegal logging activities has yet to be arrested or charged. In the same province the “HMH” company has commenced the logging of a 5,000 hectare swathe in an illegal operation that is being protected by government soldiers.

“More and more Cambodians are being pushed into poverty by the uncontrolled pillaging of Cambodia’s forests and natural resources, which are vital to most Cambodians’ livelihood,” said Adams. “At the same time, people in rural areas are becoming more afraid to speak out in an increasingly repressive environment.”

Seizure of land by foreign firms, legislators and people with family or business connections to high-ranking government officials is on the rise in the provinces. Last month, for example, villagers in Koh Kong province peacefully protesting a land concession controlled by Cambodia People’s Party Senator Ly Yong Phat were attacked by military police. Authorities prevented human rights workers investigating the incident from speaking to the villagers. At 20,000 hectares, Ly Yong Phat’s concession is twice the maximum size permitted by the Land Law.

In Phnom Penh, the government has forcibly evicted thousands of families from entire settlements this year, claiming the land is owned by private companies or needed for public projects. Many of these poor urban families have lived in their settlements for more than a decade. Police have used unnecessary force during many of the evictions. In June, for example, 600 armed military police officers forcibly evicted Sambok Chap villagers. Afterwards, the 1,000 displaced families were dumped at a one-hectare relocation site 20 kilometers from Phnom Penh. It lacked running water, sanitation facilities, houses, electricity, and schools, and was prone to flooding. (To see a photo essay of the forced evictions, click here)

“For many Cambodians, having land to farm or a place to live near jobs and services is a matter of life or death,” said Sidiki Kaba, President of the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH). “Donors can either stand idly by while Cambodian citizens become increasingly landless, impoverished and disenfranchised, or they can insist on concrete action. For a start, they must push the government to declare a moratorium on evictions until it adopts comprehensive policies on housing, land tenure, and relocation which truly protects the rights and livelihoods of Cambodia’s poor.”

Yash Ghai, the UN Special Representative for Human Rights in Cambodia, recently urged the donor community to become much more proactive in ensuring that the aid they give actually helps the people:

Ambassadors from donor countries – which provide half of Cambodia’s annual budget – are scheduled to meet in Phnom Penh on Thursday for a half-yearly review of the government’s progress in meeting reform targets set at their last meeting.

The statement, issued jointly by Human Rights Watch, Global Witness, FORUM-ASIA, the Asian Human Rights Commission, and the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), follows up on a letter the group sent to donors earlier this year, prior to their annual Consultative Group (CG) meeting in March.

“For more than a decade, the Cambodian government has taken donors for a ride by promising reforms but failing to deliver,” said Brad Adams, Asia director at Human Rights Watch. “It’s not the donors who are hurt by attacks on labor activists, a politicized judiciary and rampant corruption. It’s Cambodia’s poor and marginalized citizens who bear the brunt of bad governance and the failure of donors to insist on change.”

The five organizations renewed their call for donors to increase their assistance through nongovernmental channels to promote human rights, development, the rule of law, counter-corruption, and media freedom. Budgetary support and development assistance to the government should be contingent on:

- Guaranteeing the rights of individuals and organizations to defend and promote human rights, including the right to peacefully criticize and protest government policies, in accordance with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the 1998 United Nations General Assembly Declaration on Human Rights Defenders.

- Repealing the defamation, libel, disinformation, incitement, and other provisions in the criminal law that criminalize freedom of expression as protected by international law.

- Creating an independent and restructured National Election Committee.

- Liberalizing electronic media ownership rules, including allowing transmitters of private, critical media to be as strong as those of pro-government private stations.

- Complying fully with 2004 Consultative Group commitments to address corruption and misuse of natural resources and other state assets. These include public disclosure of information concerning management of land, forests, mineral deposits and fisheries, as well as the location of military development zones.

- Meeting its commitment to cancel concessions and exploitation permits that have been granted illegally.

- Passing asset disclosure and anti-corruption laws that meet international standards and appointing an independent, international external auditor for government finances.

“Pledges by the Cambodian government to reduce poverty are meaningless if rhetoric is not matched by action,” said Patrick Alley from Global Witness. “Donors should make it clear that continued assistance will depend on the Cambodian government keeping its promises. Otherwise, the whole exercise of setting benchmarks for reform is a sham.”

Cambodians continue to fall into poverty and landlessness because the government refuses to end bald-faced corruption by officials and reform a court system that is used to advance political agendas, silence critics, and strip people of their land. At the last meeting, donors insisted on the adoption of a strong anti-corruption law as the minimum that they expected from the government, but even this modest step – in the works since 1995 – has not taken place.

Since the March CG meeting, senior government officials have continued to issue illegal contracts enabling private companies to clear-cut the country’s forests under the guise of economic land concessions, damaging local people’s livelihoods and circumventing the moratorium on cutting in logging concessions. This is in violation of Cambodia’s Land Law and a recent sub-decree on economic land concessions, both of which were drafted with support from international donors.

Meanwhile, the government has yet to deliver on its repeated commitments to publicly disclose information on economic land concessions and cancel those that have been granted illegally. This lack of transparency further reduces the already minimal scope Cambodians have to hold officials to account.

“There’s a huge gap between reforms promised by the Cambodian government at each donor meeting and the ongoing hardships faced by Cambodian citizens every day,” said Anselmo Lee, executive director of FORUM-ASIA. “Donors must stop sending mixed messages to the Cambodian government by demanding reforms while increasing aid. This hypocrisy must end now.”

Government crackdowns on freedom of speech and public assembly – together with arrests and harassment of communities seeking to maintain their access to land and natural resources – has created a repressive atmosphere, prohibiting many citizens from airing their grievances in public.

Syndicates comprising relatives of senior officials and elite military units continue to conduct illegal logging operations with impunity in several provinces, notably Kompong Thom. A relative of the prime minister who shot at two community forestry activists in Tumring Commune last year after they attempted to stop his illegal logging activities has yet to be arrested or charged. In the same province the “HMH” company has commenced the logging of a 5,000 hectare swathe in an illegal operation that is being protected by government soldiers.

“More and more Cambodians are being pushed into poverty by the uncontrolled pillaging of Cambodia’s forests and natural resources, which are vital to most Cambodians’ livelihood,” said Adams. “At the same time, people in rural areas are becoming more afraid to speak out in an increasingly repressive environment.”

Seizure of land by foreign firms, legislators and people with family or business connections to high-ranking government officials is on the rise in the provinces. Last month, for example, villagers in Koh Kong province peacefully protesting a land concession controlled by Cambodia People’s Party Senator Ly Yong Phat were attacked by military police. Authorities prevented human rights workers investigating the incident from speaking to the villagers. At 20,000 hectares, Ly Yong Phat’s concession is twice the maximum size permitted by the Land Law.

In Phnom Penh, the government has forcibly evicted thousands of families from entire settlements this year, claiming the land is owned by private companies or needed for public projects. Many of these poor urban families have lived in their settlements for more than a decade. Police have used unnecessary force during many of the evictions. In June, for example, 600 armed military police officers forcibly evicted Sambok Chap villagers. Afterwards, the 1,000 displaced families were dumped at a one-hectare relocation site 20 kilometers from Phnom Penh. It lacked running water, sanitation facilities, houses, electricity, and schools, and was prone to flooding. (To see a photo essay of the forced evictions, click here)

“For many Cambodians, having land to farm or a place to live near jobs and services is a matter of life or death,” said Sidiki Kaba, President of the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH). “Donors can either stand idly by while Cambodian citizens become increasingly landless, impoverished and disenfranchised, or they can insist on concrete action. For a start, they must push the government to declare a moratorium on evictions until it adopts comprehensive policies on housing, land tenure, and relocation which truly protects the rights and livelihoods of Cambodia’s poor.”

Yash Ghai, the UN Special Representative for Human Rights in Cambodia, recently urged the donor community to become much more proactive in ensuring that the aid they give actually helps the people:

The international community … bears a special responsibility to support Cambodia and its people in their quest for justice and accountability. But its engagement must be based on a hardheaded analysis of the underlying causes of the sorry state of human rights and social justice in Cambodia ...“It’s time the donors asked themselves some hard questions – are their efforts ensuring a rule of law that protects the interests of ordinary Cambodians from the predations of corrupt officials?” said Basil Fernando, executive director of the Asian Human Rights Commission. “Or are they simply wasting taxpayers’ money and abandoning their responsibilities to the poor and disenfranchised who they claim they want to help?”

With aid-giving comes the responsibility to ensure that it helps the people. The donor and international community in Cambodia must give far higher priority to human rights and actively advocate for their implementation. They must energetically support poor and powerless communities and Cambodian nongovernmental organizations defending and working for human rights. It is not sufficient to rely on technical assistance and capacity building, or emphasize adherence to human rights treaties and protocols (useful as these are). Nor are new laws or suddenly created institutions the panacea, for the Government has disregarded laws, or through abuse, turned them to its own partisan advantage …

2 comments:

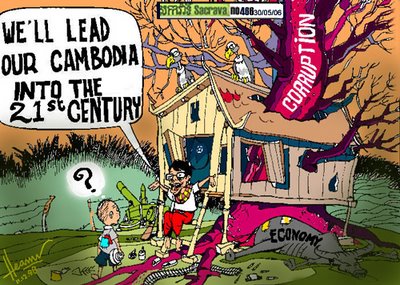

Fine imagination Mr. Sacrava, but only to fine out that is the true picture of roots of destruction that destroy our homeland today. You are one cool guy!

Mr. Ghai is correct!

HS said: you cut aid, not me to die, people die!

CPP said: les chiens aboient, la caravane passes!

But:

"use strong medecines to cure serious diseases"

Post a Comment