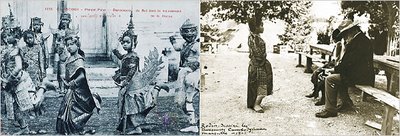

Dancers of the Royal Ballet of Cambodia, left, inspired Rodin so much that he followed the company from Paris to Marseilles in 1906 to sketch them.

Dancers of the Royal Ballet of Cambodia, left, inspired Rodin so much that he followed the company from Paris to Marseilles in 1906 to sketch them.  Forty of Rodin’s drawings of classical Cambodian dancers, like the two above, visit the National Museum in Cambodia in a wing renovated for the show.

Forty of Rodin’s drawings of classical Cambodian dancers, like the two above, visit the National Museum in Cambodia in a wing renovated for the show.By ERIKA KINETZ

The New York Times

PHNOM PENH, Cambodia, Dec. 26 — In July 1906 Auguste Rodin went to the palace of the president of France for a garden party featuring the dancers of the Royal Ballet of Cambodia.

Paris was abuzz. King Sisowath of Cambodia was making his first state visit to France and had taken with him his troupe of royal dancers, girls with strange short hair and agile feet who had been performing to rave reviews at the Colonial Exposition in Marseille.

Rodin, 66 at the time and already famous as a sculptor, showed up with a ticket but no tie. He was turned away, furious. He managed to see the dancers perform in the Bois de Boulogne a few days later. What he saw was so pure and startling that it sparked in him a kind of fever he could only describe as love.

“I contemplated them in ecstasy,” he said at the time, according to the exhibition catalog.

Rodin followed the dancers back to Marseille so precipitately that he left his art supplies behind and had to buy butcher paper from a grocer to draw on. “I would have followed them all the way to Cairo,” he said.

From this brief encounter — Rodin spent less than a week in Marseille — came 150 of his most famous drawings. Forty are now on display for the first time in Cambodia at the National Museum here. (The drawings were exhibited at the Rodin Museum in Paris this year.)

“Here you have a real exchange of two authentic traditions,” said Christina Buley-Uribe, a curator from the Rodin Museum in Paris who was here recently to hang the show, which opened on Saturday and runs through Feb. 11. “It is the encounter of Rodin’s modernity and this very traditional dance.”

The French government is sponsoring the exhibition to celebrate the 100th anniversary of King Sisowath’s visit. To house the fragile works on paper, a wing of the National Museum has been renovated and a room with temperature and humidity controls room constructed. It is the first in Cambodia capable of housing delicate artwork, according to officials from the museum and the French Embassy.

The entire project cost the French government about $200,000, said Fabyène Mansencal, the first secretary at the French Embassy here. The French are even paying for the show’s air-conditioning.

“It’s our souvenir from the colonial period,” said Khun Samen, the director of the National Museum. “Today the French are our friends. Not control. Cooperation.” (Cambodia, which became independent in 1953, was a French protectorate in 1863 and a French colony in 1887, as part of Indochina.)

Most of the National Museum’s collection consists of stone and bronze objects, sturdy stuff capable of handling a little weather. Mr. Khun said that once the Rodin exhibition is over, he plans to use the new room for conferences and film screenings, and perhaps to show art on loan from museums abroad.

In preparation for the current show, curators from the Rodin Museum came here and worked with dancers to match the gestures in the drawings with the gestures of the dance. “Some drawings were precise,” Ms. Buley-Uribe said. “Others were completely unrecognizable by Cambodians. They didn’t know what it was.”

Classical Cambodian dance is a deeply conservative form. In 1906 it was almost exclusively a function of the court. The dancers lived at the Royal Palace and performed at the king’s pleasure, mostly for dignitaries and royal rituals, like marriages or funerals.

The dance itself unfolds in a slow succession of distinctive, almost mimetic postures that have changed little over time. Classical dances were not born of a single artistic mind; they were retellings of communal myths, commissioned by the royal family and created by committee.

Writing in the exhibition catalog, Proeung Chhieng, the vice rector at the Royal University of Fine Arts here, said that Cambodia’s dance was a tradition with a precise choreographic language that “excludes any improvisation or variation.”

In contrast, Rodin, as a modern, Western artist, improvised. He used the dancers as the basis of his own invention, placing in their hands small statues and palms — Greek allegories of victory — and washing them in colors of an Italian fresco: ocher, rust and blue.

“The exotic aspect of the Cambodian dancers is zero,” Ms. Buley-Uribe said. “He’s interested in their gestures and in his ability to assimilate them for his own purpose.”

Soth Sam On, 77, was a member of the Royal Ballet from 1935 until the Khmer Rouge took over in 1975. The day the show opened, she visited the museum. Now a frail woman with large, watery eyes and a shock of white hair, she pressed her fingertips to the wall and peered intently at one of the drawings.

“If you look to the position of the arm, it is not correct,” she said. “It is too high. But the energy is there.”

Some of the drawings, she said, are of unfinished movements. “For me as a dancer, my teacher wanted me to be exact, to finish,” she said. “The drawings have loose lines, but they are very beautiful.”

Like many Cambodians, Ms. Soth had never heard of Rodin. Six students from the Royal University of Fine Arts who attended the opening gala of the exhibition had not heard of him either. Neither, for that matter, had the director of the National Museum, until, he said, curators from the Rodin Museum approached him about doing the show.

Some of Rodin’s drawings have an unfinished quality that strikes some Cambodians as “lazy” or even “ugly.”

“The art of Cambodia is very codified,” said Sisowath Tesso, the great-great-grandson of King Sisowath. “This vision of Rodin is very different. It is strange, sometimes, for Cambodian eyes.”

Mr. Sisowath, who divides his time between France and Cambodia, added: “It can help Cambodians have another vision of their own art. If young people come here, they can say, ‘Why not have another vision about our own culture and be creative?’ ”

Paris was abuzz. King Sisowath of Cambodia was making his first state visit to France and had taken with him his troupe of royal dancers, girls with strange short hair and agile feet who had been performing to rave reviews at the Colonial Exposition in Marseille.

Rodin, 66 at the time and already famous as a sculptor, showed up with a ticket but no tie. He was turned away, furious. He managed to see the dancers perform in the Bois de Boulogne a few days later. What he saw was so pure and startling that it sparked in him a kind of fever he could only describe as love.

“I contemplated them in ecstasy,” he said at the time, according to the exhibition catalog.

Rodin followed the dancers back to Marseille so precipitately that he left his art supplies behind and had to buy butcher paper from a grocer to draw on. “I would have followed them all the way to Cairo,” he said.

From this brief encounter — Rodin spent less than a week in Marseille — came 150 of his most famous drawings. Forty are now on display for the first time in Cambodia at the National Museum here. (The drawings were exhibited at the Rodin Museum in Paris this year.)

“Here you have a real exchange of two authentic traditions,” said Christina Buley-Uribe, a curator from the Rodin Museum in Paris who was here recently to hang the show, which opened on Saturday and runs through Feb. 11. “It is the encounter of Rodin’s modernity and this very traditional dance.”

The French government is sponsoring the exhibition to celebrate the 100th anniversary of King Sisowath’s visit. To house the fragile works on paper, a wing of the National Museum has been renovated and a room with temperature and humidity controls room constructed. It is the first in Cambodia capable of housing delicate artwork, according to officials from the museum and the French Embassy.

The entire project cost the French government about $200,000, said Fabyène Mansencal, the first secretary at the French Embassy here. The French are even paying for the show’s air-conditioning.

“It’s our souvenir from the colonial period,” said Khun Samen, the director of the National Museum. “Today the French are our friends. Not control. Cooperation.” (Cambodia, which became independent in 1953, was a French protectorate in 1863 and a French colony in 1887, as part of Indochina.)

Most of the National Museum’s collection consists of stone and bronze objects, sturdy stuff capable of handling a little weather. Mr. Khun said that once the Rodin exhibition is over, he plans to use the new room for conferences and film screenings, and perhaps to show art on loan from museums abroad.

In preparation for the current show, curators from the Rodin Museum came here and worked with dancers to match the gestures in the drawings with the gestures of the dance. “Some drawings were precise,” Ms. Buley-Uribe said. “Others were completely unrecognizable by Cambodians. They didn’t know what it was.”

Classical Cambodian dance is a deeply conservative form. In 1906 it was almost exclusively a function of the court. The dancers lived at the Royal Palace and performed at the king’s pleasure, mostly for dignitaries and royal rituals, like marriages or funerals.

The dance itself unfolds in a slow succession of distinctive, almost mimetic postures that have changed little over time. Classical dances were not born of a single artistic mind; they were retellings of communal myths, commissioned by the royal family and created by committee.

Writing in the exhibition catalog, Proeung Chhieng, the vice rector at the Royal University of Fine Arts here, said that Cambodia’s dance was a tradition with a precise choreographic language that “excludes any improvisation or variation.”

In contrast, Rodin, as a modern, Western artist, improvised. He used the dancers as the basis of his own invention, placing in their hands small statues and palms — Greek allegories of victory — and washing them in colors of an Italian fresco: ocher, rust and blue.

“The exotic aspect of the Cambodian dancers is zero,” Ms. Buley-Uribe said. “He’s interested in their gestures and in his ability to assimilate them for his own purpose.”

Soth Sam On, 77, was a member of the Royal Ballet from 1935 until the Khmer Rouge took over in 1975. The day the show opened, she visited the museum. Now a frail woman with large, watery eyes and a shock of white hair, she pressed her fingertips to the wall and peered intently at one of the drawings.

“If you look to the position of the arm, it is not correct,” she said. “It is too high. But the energy is there.”

Some of the drawings, she said, are of unfinished movements. “For me as a dancer, my teacher wanted me to be exact, to finish,” she said. “The drawings have loose lines, but they are very beautiful.”

Like many Cambodians, Ms. Soth had never heard of Rodin. Six students from the Royal University of Fine Arts who attended the opening gala of the exhibition had not heard of him either. Neither, for that matter, had the director of the National Museum, until, he said, curators from the Rodin Museum approached him about doing the show.

Some of Rodin’s drawings have an unfinished quality that strikes some Cambodians as “lazy” or even “ugly.”

“The art of Cambodia is very codified,” said Sisowath Tesso, the great-great-grandson of King Sisowath. “This vision of Rodin is very different. It is strange, sometimes, for Cambodian eyes.”

Mr. Sisowath, who divides his time between France and Cambodia, added: “It can help Cambodians have another vision of their own art. If young people come here, they can say, ‘Why not have another vision about our own culture and be creative?’ ”

2 comments:

Khmer Artists should learn more outside of Khmer Arts....to explore more to the level of world stage artistry.

Bun H.ung

ex Fine Arts Khmer Student

1965-1975

Cambodian loves French arts and designs. it looks to me that we share the same equal passion.

I'm Cambodian and when it comes to French arts and galleries stuff , give them me!!!!!!!!

I want them and all. French have an undeniable- unique and breath taking taste. Right now, they are the standard of the world.

Post a Comment