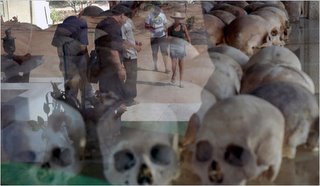

Tourists were reflected on a shrine to Khmer Rouge victims near the Choeung Ek Genocidal Center outside of Phnom Penh. (Mak Remissa/European Pressphoto Agency)

Tourists were reflected on a shrine to Khmer Rouge victims near the Choeung Ek Genocidal Center outside of Phnom Penh. (Mak Remissa/European Pressphoto Agency)Thursday, January 25, 2007

Unwieldy court further complicates long-delayed Khmer Rouge trial

By Seth Mydans

Posted by the International Herald Tribune

PHNOM PENH

The Cambodian judges were on one side and the foreign judges on the other this week in a dispute that captures a decade of difficulties in bringing to trial the last surviving leaders of the murderous Khmer Rouge.

If they cannot agree on procedural rules soon, analysts and officials at the tribunal say, some foreign judges could walk out, casting a further shadow over a process that some critics say is already so compromised as to be of doubtful value.

Seventeen Cambodians and 12 foreigners took office as judges and prosecutors last July, inaugurating a United Nations-sponsored process that mixes Cambodian law with international standards of justice.

It is an awkward formula made all the more questionable by the involvement of poorly trained Cambodian judges who were appointed by and are answerable to Prime Minister Hun Sen.

Pragmatists say that a flawed trial is better than none at all and that there is no choice but to proceed with the tribunal you've got rather than the tribunal you might wish to have.

Three decades have already passed since the Khmer Rouge ruled Cambodia, causing the deaths of 1.7 million people through killings, torture, starvation and overwork in a regime that lasted from 1975 to 1979.

The potential defendants are aging and some have died, notably the Khmer Rouge leader, Pol Pot, in 1998. The trial targets top leaders and "those most responsible" for the crimes and is expected to focus on at most a dozen defendants.

A handful of names are generally mentioned as potential defendants, only one of whom is in custody, with the remainder living freely in Cambodia.

The foreign prosecutor, a Canadian named Robert Petit, has been pursuing the evidence vigorously and has not said where it is leading him.

In an interview, he said he was ready to propose his first indictments once the judges have formalized the rules at a plenary session tentatively set for March. A trial might then begin by the end of the year.

A rules committee of nine judges is attempting to resolve the differences now. Sean Visoth, the tribunal's Cambodian coordinator, said: "If there is no compromise and there is no plenary, the international judges will walk away."

The delay has revived a familiar concern that Hun Sen might not in fact want the trial to proceed and might be throwing up the latest in a long series of roadblocks that have stalled it over the years.

Among other things, he is believed to be under pressure from China, which does not want to see a trial that would be likely to demonstrate its close ties to the Khmer Rouge regime.

Cambodia and the United Nations reached agreement on the structure of the mixed tribunal in 2003 after years of difficult negotiations that involved both technical and political differences.

Those differences remained at the heart of the disagreements that have stalled the trial since last November, according to experts on the tribunal.

There are more than 100 sometimes complicated procedural rules to be agreed upon. But the core disputes appear to involve a fundamental, long- running issue: the independence of the trial from Cambodian political manipulation.

On the Cambodian side, an important issue is control, the U.S. ambassador, Joseph Mussomeli, said. "The government in general tries to keep tight control over the judiciary and anything that could have negative consequences," he said.

The first concern is the scope of indictments in a country where the politics of the present remain tangled in the past. Some former middle-ranking Khmer Rouge are prominent in the current government, including Hun Sen — although experts say he is not culpable.

Other potential defendants may have powerful patrons who seek to protect them from indictment.

One point of contention among the judges, according to people close to the negotiation, is an extremely complex provision that would in effect allow an indictment to proceed without the agreement of the Cambodian side.

That provision is one of several balancing acts in the tribunal's supermajority system that at most junctures allows foreign and Cambodian judges to cast what amount to vetoes over one another's decisions.

In addition, the Cambodian side is seeking to limit the right of defendants to be represented in court by foreign lawyers, which it says is a violation of Cambodian legal sovereignty.

Foreign analysts say that the Cambodian concern is that aggressive foreign lawyers would be independent of any political guidance and could send the case in unpredictable directions.

A British lawyer, Rupert Skilbeck, has already set up a Defense Office to coordinate the work of individual lawyers once they are hired. He said that without the right to select their own lawyers defendants would be placed at a disadvantage.

"It's important that the trials are very fair because if they're seen as show trials, then there will be no justice," he said in November, speaking to the Cambodian Bar Association, which is closely allied with Hun Sen and which opposes participation by foreign lawyers.

Mussomeli said that the Cambodian government, accustomed to controlling the judiciary, might be reacting defensively to Petit, who has taken on his job as prosecutor with an energy and independence that is unfamiliar here.

In the interview, Petit sought to calm these concerns, saying he was aware of the sensitivity of his role and of the possibility that the tribunal could be derailed by an overly aggressive prosecution.

"We have to apply the law in the context of Cambodia," he said. "I'm not stupid. You have to exercise discretion."

Petit has been involved in international tribunals in Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Kosovo and East Timor, and he said that he understood that in cases like these it is not possible to follow the law blindly, without reference to its context.

"We all have a sense of our responsibilities," he said. "Our primary responsibility is to deliver justice to the victims of these crimes." That would not be possible, he said, if the process was shut down for any reason.

"Having a right and exercising it with good judgment is two different things," he said.

He said he did not yet know how many cases he would forward to the next level of the tribunal, the investigating judges, who are to issue indictments.

"In this particular tribunal there are very specific expectations," he said. "Everyone knows what happened. We've got the evidence there, you just have to pick it up and carry it into court — well, it doesn't work that way.

"We have to grasp events of great magnitude that happened 30 years ago and be legally and morally convinced that we have cases against individual people," he said.

The Cambodian judges were on one side and the foreign judges on the other this week in a dispute that captures a decade of difficulties in bringing to trial the last surviving leaders of the murderous Khmer Rouge.

If they cannot agree on procedural rules soon, analysts and officials at the tribunal say, some foreign judges could walk out, casting a further shadow over a process that some critics say is already so compromised as to be of doubtful value.

Seventeen Cambodians and 12 foreigners took office as judges and prosecutors last July, inaugurating a United Nations-sponsored process that mixes Cambodian law with international standards of justice.

It is an awkward formula made all the more questionable by the involvement of poorly trained Cambodian judges who were appointed by and are answerable to Prime Minister Hun Sen.

Pragmatists say that a flawed trial is better than none at all and that there is no choice but to proceed with the tribunal you've got rather than the tribunal you might wish to have.

Three decades have already passed since the Khmer Rouge ruled Cambodia, causing the deaths of 1.7 million people through killings, torture, starvation and overwork in a regime that lasted from 1975 to 1979.

The potential defendants are aging and some have died, notably the Khmer Rouge leader, Pol Pot, in 1998. The trial targets top leaders and "those most responsible" for the crimes and is expected to focus on at most a dozen defendants.

A handful of names are generally mentioned as potential defendants, only one of whom is in custody, with the remainder living freely in Cambodia.

The foreign prosecutor, a Canadian named Robert Petit, has been pursuing the evidence vigorously and has not said where it is leading him.

In an interview, he said he was ready to propose his first indictments once the judges have formalized the rules at a plenary session tentatively set for March. A trial might then begin by the end of the year.

A rules committee of nine judges is attempting to resolve the differences now. Sean Visoth, the tribunal's Cambodian coordinator, said: "If there is no compromise and there is no plenary, the international judges will walk away."

The delay has revived a familiar concern that Hun Sen might not in fact want the trial to proceed and might be throwing up the latest in a long series of roadblocks that have stalled it over the years.

Among other things, he is believed to be under pressure from China, which does not want to see a trial that would be likely to demonstrate its close ties to the Khmer Rouge regime.

Cambodia and the United Nations reached agreement on the structure of the mixed tribunal in 2003 after years of difficult negotiations that involved both technical and political differences.

Those differences remained at the heart of the disagreements that have stalled the trial since last November, according to experts on the tribunal.

There are more than 100 sometimes complicated procedural rules to be agreed upon. But the core disputes appear to involve a fundamental, long- running issue: the independence of the trial from Cambodian political manipulation.

On the Cambodian side, an important issue is control, the U.S. ambassador, Joseph Mussomeli, said. "The government in general tries to keep tight control over the judiciary and anything that could have negative consequences," he said.

The first concern is the scope of indictments in a country where the politics of the present remain tangled in the past. Some former middle-ranking Khmer Rouge are prominent in the current government, including Hun Sen — although experts say he is not culpable.

Other potential defendants may have powerful patrons who seek to protect them from indictment.

One point of contention among the judges, according to people close to the negotiation, is an extremely complex provision that would in effect allow an indictment to proceed without the agreement of the Cambodian side.

That provision is one of several balancing acts in the tribunal's supermajority system that at most junctures allows foreign and Cambodian judges to cast what amount to vetoes over one another's decisions.

In addition, the Cambodian side is seeking to limit the right of defendants to be represented in court by foreign lawyers, which it says is a violation of Cambodian legal sovereignty.

Foreign analysts say that the Cambodian concern is that aggressive foreign lawyers would be independent of any political guidance and could send the case in unpredictable directions.

A British lawyer, Rupert Skilbeck, has already set up a Defense Office to coordinate the work of individual lawyers once they are hired. He said that without the right to select their own lawyers defendants would be placed at a disadvantage.

"It's important that the trials are very fair because if they're seen as show trials, then there will be no justice," he said in November, speaking to the Cambodian Bar Association, which is closely allied with Hun Sen and which opposes participation by foreign lawyers.

Mussomeli said that the Cambodian government, accustomed to controlling the judiciary, might be reacting defensively to Petit, who has taken on his job as prosecutor with an energy and independence that is unfamiliar here.

In the interview, Petit sought to calm these concerns, saying he was aware of the sensitivity of his role and of the possibility that the tribunal could be derailed by an overly aggressive prosecution.

"We have to apply the law in the context of Cambodia," he said. "I'm not stupid. You have to exercise discretion."

Petit has been involved in international tribunals in Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Kosovo and East Timor, and he said that he understood that in cases like these it is not possible to follow the law blindly, without reference to its context.

"We all have a sense of our responsibilities," he said. "Our primary responsibility is to deliver justice to the victims of these crimes." That would not be possible, he said, if the process was shut down for any reason.

"Having a right and exercising it with good judgment is two different things," he said.

He said he did not yet know how many cases he would forward to the next level of the tribunal, the investigating judges, who are to issue indictments.

"In this particular tribunal there are very specific expectations," he said. "Everyone knows what happened. We've got the evidence there, you just have to pick it up and carry it into court — well, it doesn't work that way.

"We have to grasp events of great magnitude that happened 30 years ago and be legally and morally convinced that we have cases against individual people," he said.

1 comment:

the best thing is to agree with the incompetence of the cambodian judges. AND expose them. use reverse psychology.

Hen Sen will never let this trail go forward... there will always be obstacle..the best way to desrive hun sen is like an octopus..

This trial is more than a show and anything else. I hope someone is making a documentary of this circus.

Post a Comment