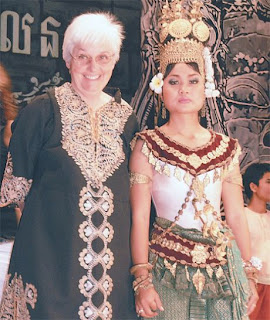

Ridgefielder Darla Shaw was photographed with one of the traditional dancers she saw perform while in Cambodia where she helped pre-school teachers learn literacy teaching techniques.

Ridgefielder Darla Shaw was photographed with one of the traditional dancers she saw perform while in Cambodia where she helped pre-school teachers learn literacy teaching techniques. Shrymon is the subject of a book that Ridgefield’s Darla Shaw is writing on a day in the life of a child in a Cambodian village. The book will be given to donors who sponsor children through the Hearts and Hands for Cambodia program.

Shrymon is the subject of a book that Ridgefield’s Darla Shaw is writing on a day in the life of a child in a Cambodian village. The book will be given to donors who sponsor children through the Hearts and Hands for Cambodia program.Apr 22, 2007

By Macklin Reid,

Ridgefield Press Staff (Connecticut, USA)

At an orphanage in one of the poorest villages of rural Cambodia, children sing “London Bridge is falling down” in English as well as their native Khmer. They play “Duck, Duck, Goose,” as the kids at any preschool in Ridgefield might. They have books and art materials, and are learning to read through some of the state-of-the-art teaching techniques used in the United States.

Behind it all is Darla Shaw, a Ridgefielder with 50 years of teaching behind her who is anything but retired.

“By the time we left, they knew our nursery rhymes, they were singing our songs, they were playing our games,” she said. “It’s amazing, in a couple of weeks time these children were so focused and excited to have us there.”

“We did things like Duck, Duck, Goose, London Bridge — all the typical things that they would have no knowledge of — the people would translate it, they would do it in English and Khmer.”

Dr. Shaw, a professor of education at Western Connecticut State University, went to Cambodia in January. She has lived in Ridgefield some 40 years and taught in the Ridgefield public schools for 38 years, before starting with WestConn 12 years ago.

Accompanying her to Cambodia were about 15 students from the graduate reading program she heads at WestConn — people in advanced studies of how reading can most effectively be taught.

Humanitarian travel

“It was a humanitarian travel program to Cambodia. It was for students, basically,” Dr. Shaw said. “But this has been my new thrust in life: humanitarian travel. I decided to go along, I feel I have expertise I can share in any country.

“No matter where you go, particularly in Third World countries, they’re looking for help with any kind of literacy, and they’ll provide an interpreter,” she said. “I did staff development there, and I’d have a translator beside me, and it worked very well.”

The first contribution the group made was in the form of supplies that they donated to the orphanage, which also functions as a kind of day care center and preschool for an impoverished village in the Cambodian countryside near Battambong.

“They never had any books, we brought over books — books in English, because they want them to learn English and Khmer,” Dr. Shaw said.

“Each of us could take two bags that were 70 pounds, so what we took was very little, except supplies and materials,” Dr. Shaw said. “...Books, markers and construction paper, any kind of art material. They don’t have any kind of educational games, educational toys — they have nothing.”

With the translators, Dr. Shaw and her students helped the workers in the orphanage learn ways to engage young students in learning to read. “I did emergent literacy — that’s like a preschool type of thing,” Dr. Shaw said.

She an her students work with the Cambodia teachers, showing them how to adapt teaching techniques from the West. “There were 150 children in the school and they had five teachers, and then I trained our students and their teachers in various literacy techniques,” she said.

At the end of the month’s stay, they put on a play. “They’d never put on any plays, or had plays, or performances. They kind of brought the kids together and made certain they had food and a playground, but they never had any kind of a cultural program.”

“As a culminating activity we put on the play ‘The Cambodian Cinderella.’ I have 75 Cinderella books in my collection and I had the Cambodian Cinderella. It’s much more violent than ours ... We kind of adapted it.”

The school also provides the children with food — a lunchtime meal — and with clothing, and toothbrushes. The children gets baths there.

“Our kids were so surprised — they bathed the kids every day,” Dr. Shaw said.

“The school is just so important to these families.”

Hearts and Hands book

As a result of the trip, Dr. Shaw is also writing a book about a day in the life of a child in the village. It will be part of the package given to donors who sign on to sponsor children through the Hearts and Hands for Cambodia program.

Dr. Shaw based the book on a day in the life of a girl, Shrymon, who wasn’t one of the orphans but comes to the orphanage and day-care center from the village where she lives with her family. Dr. Shaw had gotten to know her because she had a badly infected burn on her leg that the American visitors helped her get properly treated. “Otherwise they just use the native potions and sometimes it gets infected,” Dr. Shaw said.

“She just had this very sad look on her face.”

But she chose Shrymon because she was told her family was typical of a poor rural Cambodians.

“Twelve to 15 people, they live in one room, particularly in the rainy season. They might have places outside, hammocks outside, they cook outside. There’s no material possessions at all. And it’s one extended family,” Dr. Shaw said.

“This particular woman had 12 children; eight of them have survived, and she’s in her early 40’s, so she will have more. When we went to visit her, she had a child at each breast.

“We had an interpreter, and we asked if she had any hopes of dreams. She just said ‘food.’ It’s just survival,” Dr. Shaw said.

“They usually only have one meal, and sometimes that meal is just like rice with water.”

Writing the book has its challenges — there’s a wide cultural gap.

“It was really very hard to write the book, and not make it a sad book,” Dr. Shaw said. “...It’s their life, and they’re not sad, really. They don’t know anything else. They have very close families, very loving relationships.”

The book is aimed at an audience of Americans — donors.

“The book is very rewarding and uplifting and it shows how a school can change the ‘a day in the life’ of the child,” Dr. Shaw said.

“When they go to the school, their whole life changes, their whole concept of what they can do, what they can be.”

The work at the orphanage village day-care center is important, Dr. Shaw said, because very few families can afford the cost of travel to and attend real schools.

“A few will go on to grade school, and the percentage that goes on after grade school is so small, 2% or 3%,” she said.

Killing fields

The work is against the backdrop of Cambodia’s recent history — the war, the Khmer Rouge, the anti-colonialist revolution that turned into a violent purge against people the revolutionaries felt were tainted by association with the West.

“I knew what went on in Cambodia, and it wasn’t that long ago,” Dr. Shaw said. “They wiped out the brightest, the best, the creative, the artisans — they killed them off. They really lost a whole generation or two. These people are starting from scratch.

“We went to the killing fields. We went to the inquisition museum. This was where they tortured the people.”

One legacy of the county’s insane years is the shattered state of many survivors.

“The people are dying off in their 40’s. Even though they weren’t killed, their health is so bad, and they’re just not living,” Dr. Shaw said.

Rotary water projects

Dr. Shaw visited places where the Sustainable Cambodia project has been working to improve rural people’s lives.

“Sustainable Cambodia,” she said. “You begin to dig wells. You begin to filter the water. You build fish hatcheries.”

Rotary International is a supporter of Sustainable Cambodia efforts, particularly the water projects, and Dr. Shaw spoke to Ridgefield’s Rotary Club on April 6.

“You see all these big boxes, that are water filtration systems, and they all say ‘Rotary International’ — there’s a big Rotary seal on them.

Sustainable Cambodia also organizes “pig passes” as a means of donors in the West helping rural villagers in a way that will be passed on and grow. “You give $40 and they get a pig,” Dr. Shaw explained.

The villager who receives the pig has an obligation. Every time the pig has a litter — usually three or four piglets — one of them is passed on to another villager. “Then he begins to raise pigs,” she said.

The Sustainable Cambodia movement is based on the idea that there must be a better model for helping the people there than building factories and making them dependent on globalized economy.

“This was the most amazing thing I saw, how they transformed entire villages,” she said. “There are all these volunteers there showing them how to raise the pigs, and organic gardens, and fish hatcheries. They’re just starting something with bees. They had a cooperative rice bin, so nobody goes hungry.”

The Ridgefield Rotary, Dr. Shaw said, is considering getting together with some other local Rotary clubs to support both the water projects that Rotary International is doing with Sustainable Cambodia, and the orphanage school that she and her WestConn students are now working with.

She was impressed with the dedication of the volunteers.

“There were people from all over, some for a year, some for six months, getting no pay, putting their own money into the process, because they cared so much,” she said.

There was great cooperation among the different aid workers and volunteers.

“Everybody knows everybody, and you sort of network and piggyback and you help each other, and I find that very rewarding,” Dr. Shaw said.

“...We’re here to help the people. What can we do to help the people? What resources do you have? What resources do we have? It’s a real sharing of resources, and how can we work cooperatively to make life better for these people.”

Founders Hall talk

On April 19 Dr. Shaw gave another presentation, this one at Founders Hall. She’ll discussed “humanitarian travel.”

“About six years ago I spent the summer with Jane Goodall in Tanzania, that’s when I got my first taste of humanitarian travel,” she said. “After that I went to Cuba. I was part of the first delegation that went in to work on literacy in the schools, maybe five years ago.

“When I went to Cuba, I saw that you can make a difference.”

Since then she’s been on trips to the Bahamas and Puerto Rico.

“I’m going to Brazil and working on a medical project during March vacation,” she said. “Then I’m going in the summer back to Puerto Rico.”

She has her WestConn education students working with social work students from Fordham on a literacy project in the Dominican Republic.

She’s also involved in work with the Lakota Indians in South Dakota. “I’m very interested in oral histories and I’m going to be working with elders. I’m taking the oral histories from the elders and training the students to make their oral history books.”

As someone old enough to retire, she admits, a lot of her work stems from a desire to keep doing things with her life.

“I’ve got to,” she said. “I see people my age sitting there. I say, “When you go, you’re going to go.’ I want to go active.”

By Macklin Reid,

Ridgefield Press Staff (Connecticut, USA)

At an orphanage in one of the poorest villages of rural Cambodia, children sing “London Bridge is falling down” in English as well as their native Khmer. They play “Duck, Duck, Goose,” as the kids at any preschool in Ridgefield might. They have books and art materials, and are learning to read through some of the state-of-the-art teaching techniques used in the United States.

Behind it all is Darla Shaw, a Ridgefielder with 50 years of teaching behind her who is anything but retired.

“By the time we left, they knew our nursery rhymes, they were singing our songs, they were playing our games,” she said. “It’s amazing, in a couple of weeks time these children were so focused and excited to have us there.”

“We did things like Duck, Duck, Goose, London Bridge — all the typical things that they would have no knowledge of — the people would translate it, they would do it in English and Khmer.”

Dr. Shaw, a professor of education at Western Connecticut State University, went to Cambodia in January. She has lived in Ridgefield some 40 years and taught in the Ridgefield public schools for 38 years, before starting with WestConn 12 years ago.

Accompanying her to Cambodia were about 15 students from the graduate reading program she heads at WestConn — people in advanced studies of how reading can most effectively be taught.

Humanitarian travel

“It was a humanitarian travel program to Cambodia. It was for students, basically,” Dr. Shaw said. “But this has been my new thrust in life: humanitarian travel. I decided to go along, I feel I have expertise I can share in any country.

“No matter where you go, particularly in Third World countries, they’re looking for help with any kind of literacy, and they’ll provide an interpreter,” she said. “I did staff development there, and I’d have a translator beside me, and it worked very well.”

The first contribution the group made was in the form of supplies that they donated to the orphanage, which also functions as a kind of day care center and preschool for an impoverished village in the Cambodian countryside near Battambong.

“They never had any books, we brought over books — books in English, because they want them to learn English and Khmer,” Dr. Shaw said.

“Each of us could take two bags that were 70 pounds, so what we took was very little, except supplies and materials,” Dr. Shaw said. “...Books, markers and construction paper, any kind of art material. They don’t have any kind of educational games, educational toys — they have nothing.”

With the translators, Dr. Shaw and her students helped the workers in the orphanage learn ways to engage young students in learning to read. “I did emergent literacy — that’s like a preschool type of thing,” Dr. Shaw said.

She an her students work with the Cambodia teachers, showing them how to adapt teaching techniques from the West. “There were 150 children in the school and they had five teachers, and then I trained our students and their teachers in various literacy techniques,” she said.

At the end of the month’s stay, they put on a play. “They’d never put on any plays, or had plays, or performances. They kind of brought the kids together and made certain they had food and a playground, but they never had any kind of a cultural program.”

“As a culminating activity we put on the play ‘The Cambodian Cinderella.’ I have 75 Cinderella books in my collection and I had the Cambodian Cinderella. It’s much more violent than ours ... We kind of adapted it.”

The school also provides the children with food — a lunchtime meal — and with clothing, and toothbrushes. The children gets baths there.

“Our kids were so surprised — they bathed the kids every day,” Dr. Shaw said.

“The school is just so important to these families.”

Hearts and Hands book

As a result of the trip, Dr. Shaw is also writing a book about a day in the life of a child in the village. It will be part of the package given to donors who sign on to sponsor children through the Hearts and Hands for Cambodia program.

Dr. Shaw based the book on a day in the life of a girl, Shrymon, who wasn’t one of the orphans but comes to the orphanage and day-care center from the village where she lives with her family. Dr. Shaw had gotten to know her because she had a badly infected burn on her leg that the American visitors helped her get properly treated. “Otherwise they just use the native potions and sometimes it gets infected,” Dr. Shaw said.

“She just had this very sad look on her face.”

But she chose Shrymon because she was told her family was typical of a poor rural Cambodians.

“Twelve to 15 people, they live in one room, particularly in the rainy season. They might have places outside, hammocks outside, they cook outside. There’s no material possessions at all. And it’s one extended family,” Dr. Shaw said.

“This particular woman had 12 children; eight of them have survived, and she’s in her early 40’s, so she will have more. When we went to visit her, she had a child at each breast.

“We had an interpreter, and we asked if she had any hopes of dreams. She just said ‘food.’ It’s just survival,” Dr. Shaw said.

“They usually only have one meal, and sometimes that meal is just like rice with water.”

Writing the book has its challenges — there’s a wide cultural gap.

“It was really very hard to write the book, and not make it a sad book,” Dr. Shaw said. “...It’s their life, and they’re not sad, really. They don’t know anything else. They have very close families, very loving relationships.”

The book is aimed at an audience of Americans — donors.

“The book is very rewarding and uplifting and it shows how a school can change the ‘a day in the life’ of the child,” Dr. Shaw said.

“When they go to the school, their whole life changes, their whole concept of what they can do, what they can be.”

The work at the orphanage village day-care center is important, Dr. Shaw said, because very few families can afford the cost of travel to and attend real schools.

“A few will go on to grade school, and the percentage that goes on after grade school is so small, 2% or 3%,” she said.

Killing fields

The work is against the backdrop of Cambodia’s recent history — the war, the Khmer Rouge, the anti-colonialist revolution that turned into a violent purge against people the revolutionaries felt were tainted by association with the West.

“I knew what went on in Cambodia, and it wasn’t that long ago,” Dr. Shaw said. “They wiped out the brightest, the best, the creative, the artisans — they killed them off. They really lost a whole generation or two. These people are starting from scratch.

“We went to the killing fields. We went to the inquisition museum. This was where they tortured the people.”

One legacy of the county’s insane years is the shattered state of many survivors.

“The people are dying off in their 40’s. Even though they weren’t killed, their health is so bad, and they’re just not living,” Dr. Shaw said.

Rotary water projects

Dr. Shaw visited places where the Sustainable Cambodia project has been working to improve rural people’s lives.

“Sustainable Cambodia,” she said. “You begin to dig wells. You begin to filter the water. You build fish hatcheries.”

Rotary International is a supporter of Sustainable Cambodia efforts, particularly the water projects, and Dr. Shaw spoke to Ridgefield’s Rotary Club on April 6.

“You see all these big boxes, that are water filtration systems, and they all say ‘Rotary International’ — there’s a big Rotary seal on them.

Sustainable Cambodia also organizes “pig passes” as a means of donors in the West helping rural villagers in a way that will be passed on and grow. “You give $40 and they get a pig,” Dr. Shaw explained.

The villager who receives the pig has an obligation. Every time the pig has a litter — usually three or four piglets — one of them is passed on to another villager. “Then he begins to raise pigs,” she said.

The Sustainable Cambodia movement is based on the idea that there must be a better model for helping the people there than building factories and making them dependent on globalized economy.

“This was the most amazing thing I saw, how they transformed entire villages,” she said. “There are all these volunteers there showing them how to raise the pigs, and organic gardens, and fish hatcheries. They’re just starting something with bees. They had a cooperative rice bin, so nobody goes hungry.”

The Ridgefield Rotary, Dr. Shaw said, is considering getting together with some other local Rotary clubs to support both the water projects that Rotary International is doing with Sustainable Cambodia, and the orphanage school that she and her WestConn students are now working with.

She was impressed with the dedication of the volunteers.

“There were people from all over, some for a year, some for six months, getting no pay, putting their own money into the process, because they cared so much,” she said.

There was great cooperation among the different aid workers and volunteers.

“Everybody knows everybody, and you sort of network and piggyback and you help each other, and I find that very rewarding,” Dr. Shaw said.

“...We’re here to help the people. What can we do to help the people? What resources do you have? What resources do we have? It’s a real sharing of resources, and how can we work cooperatively to make life better for these people.”

Founders Hall talk

On April 19 Dr. Shaw gave another presentation, this one at Founders Hall. She’ll discussed “humanitarian travel.”

“About six years ago I spent the summer with Jane Goodall in Tanzania, that’s when I got my first taste of humanitarian travel,” she said. “After that I went to Cuba. I was part of the first delegation that went in to work on literacy in the schools, maybe five years ago.

“When I went to Cuba, I saw that you can make a difference.”

Since then she’s been on trips to the Bahamas and Puerto Rico.

“I’m going to Brazil and working on a medical project during March vacation,” she said. “Then I’m going in the summer back to Puerto Rico.”

She has her WestConn education students working with social work students from Fordham on a literacy project in the Dominican Republic.

She’s also involved in work with the Lakota Indians in South Dakota. “I’m very interested in oral histories and I’m going to be working with elders. I’m taking the oral histories from the elders and training the students to make their oral history books.”

As someone old enough to retire, she admits, a lot of her work stems from a desire to keep doing things with her life.

“I’ve got to,” she said. “I see people my age sitting there. I say, “When you go, you’re going to go.’ I want to go active.”

1 comment:

Beautiful origional design of Apsara costume and not too much fake stuff like it was from Thailand. Great job ladies!

Ordinary Khmers

Post a Comment