King Sihamoni of Cambodia (R) (Photo: AP)

King Sihamoni of Cambodia (R) (Photo: AP)

Boston Globe (Massachusetts, USA)The tumultuous past two months in world politics have brought a surprise with them: Suddenly, monarchy seems relevant again.

In Belgium, where the fragile government constantly is on the verge of collapse, King Albert II has been essential in trying to prevent its dissolution, mediating between leading politicians and pushing them back to the bargaining table. After Britain’s recent election, as politicians from the Labor, Conservative, and Liberal Democrat parties struggled to negotiate a ruling coalition, Queen Elizabeth’s presence reminded Britons that the country retained institutions that would prevent it from really melting down.

And most notably, in Thailand, the chaos that has ruled the streets of Bangkok stems partly from fear over the country’s future after the eventual death of increasingly frail 82-year-old King Bhumibol Adulyadej, who has helped resolve past political crises by forcing the leaders of the army and the demonstrators to meet and reconcile. Without him, notes James Ockey of the University of Canterbury in New Zealand, “Thailand may not be able to resolve future crises without major conflict.”

The idea of a monarch may seem like an anachronism in a 21st-century democracy, a relic of an earlier era in which a small elite intermarried and ruled much of the world, while most average people had no say. And to be sure, in states where kings and sultans still actually rule, like Brunei, Jordan, and Morocco, monarchs can be every bit as oppressive and opaque as any other dictatorship. Morocco’s King Mohamed VI, for example, presides over “repressive legislation to punish and imprison peaceful opponents,” according to Human Rights Watch. In Brunei, Jefri, the brother of the ruling sultan, allegedly embezzled billions in state funds, which he spent on some 2,000 cars and a lasciviously named royal yacht, among other items.

But in Europe and parts of Asia, many politicians, political scientists, and citizens have lately developed greater respect for the positive role a constitutional monarch can play in democracy. As in Belgium, monarchs can be arbiters of last resort when elected politicians cannot resolve deep divisions. They can offer their nations a unifying figure to prevent political crises from spiraling into something worse. And in an era of partisanship and diminished individual rights, monarchs can serve as a means of stability in a democracy that might otherwise tear itself apart. A.W. Purdue, author of the book “Long to Reign?”, argues that a king or queen “enables change to take place within a frame of continuity.”

Some political scientists have even argued for reviving defunct monarchies in the interest of democracy, especially in developing nations where monarchs could serve as figures of national unity to prevent ethnic and tribal bloodletting. Cambodia did so in the early 1990s following its civil wars, and the king helped inspire average Cambodians and heal wounds after the Khmer Rouge era. After the toppling of the Taliban in 2001, Afghanistan welcomed back former king Zahir Shah to launch the Loya Jirga and serve as a figure of unity as political parties bargained to build Afghan democracy. In Iraq, Sharif Ali bin Hussein, a descendant of the last monarch, has begun publicly arguing that a constitutional monarchy could help reduce the vicious ethnic and sectarian divides roiling the country. In Laos, where people can see the Thai monarchy on Thai television broadcasts, the exiled royal family has become a rallying point for some opponents of the authoritarian government. Southeast Asia academic Michael Vatikiotis argues, in an essay pushing for a return of the crown in neighboring Burma, that monarchy provided a unifying factor in that diverse society — a unifier ripped away during British colonial rule and never effectively replaced.

“The forlorn hope of progressive political change in Burma using all modern means,” he writes, “suggests that reaching back in time and resurrecting the long-dismantled monarchy could provide a prescription.”

Although the House of Windsor dominates global media coverage of monarchy, in reality 12 European countries still have monarchs, as do Cambodia, Japan, Thailand, Malaysia, Bhutan, and other nations. Despite occasional republican movements that attempt to end the monarchy, polls show strong support for the crown in nearly every nation that has one. In the Netherlands, 70 percent of respondents in one poll wanted to retain the monarchy; in Spain, 65 percent of respondents supported it; in Japan, the number was 82 percent. In many of these countries, poll respondents have more respect for the monarchy than any other public institution.

Many modernizing countries have found that a monarch provides a source of authority and national identity that stands apart from political squabbles. He or she can serve simply as a figurehead, or more substantively as a kind of independent power center that can check the worst impulses of elected politicians, in the way that a Supreme Court or House of Lords might.

Although a ceremonial president can fill this role, as in Israel or Germany, the monarch has a unique claim on the public imagination. Neil Blain, an expert on modern monarchies at the University of Stirling in Britain, says the monarch’s symbols, like the scepter and crown, can’t be replicated by a ceremonial president. The queen, he says, “attests, however mythically, to the country’s political stability and enduring historical foundations.”

“The English do not wish to see the queen on a bicycle,” he says, “because from where people stand here she looks just right in a Rolls-Royce Phantom or better still, a horse-drawn carriage.”

In developing nations, modern monarchs can do more than provide links to the past — they can help usher in democracy. In Bhutan, King Jigme Singye Wangchuck pushed his once-isolated country toward its first truly democratic elections. In Spain, King Juan Carlos midwifed a new Spanish democracy after dictator Francisco Franco’s death. In Cambodia, King Norodom Sihanouk returned to the country after the wars of the 1970s and 1980s and helped oversee a transition to democracy in the 1990s that brought the country a vibrant, if sometimes rough and bloody, democracy.

Some of these monarchs also helped bring economic and cultural modernization. The royals of Bhutan have prodded their citizens to embrace the Internet, satellite television, international trade, and other modern changes. Saudi Arabia’s King Abdullah, though not a constitutional monarch, has been credited with pushing for social and economic reforms that have diluted the power of the conservative religious establishment and pushed the kingdom to invest in science and technology education.

European monarchy experts also now see a growing role for kings and queens at a time when countries are becoming more diverse. As democracies take in more and more immigrants, and countries give up some of their national identities to superstructures like the European Union, these changes can make national unity more difficult, and a monarch can serve to welcome newcomers and help them feel like citizens.

Sweden’s king, Carl XVI Gustaf, for example, has used the monarchy to integrate immigrants. In one famous speech, he said that “new Swedish citizens...have come here from countries all over the world...under these circumstances it is precisely the strength of the monarchy that the king can be an impartial and uniting symbol.” The Netherlands’ queen, Beatrix, has used royal speeches to call for tolerance at a time when right-wing anti-Islamic politicians have made headway among the Dutch public.

Scholars of monarchy also suggest that, in an era of tightening internal security and control, when elected politicians are amassing previously unheard-of powers and courts are loath to challenge them, a monarch can safeguard public freedom. Eamonn Butler, director of the Adam Smith Institute, a think tank in London, recently argued in the Financial Times that Queen Elizabeth has stood aside too often while the prime minister has become too powerful, but that she remains a figure, under the British constitution, who could check the executive’s power. “The only solution is to make our current constitution work,” Butler wrote. “It certainly means having a monarch who is prepared to intervene on behalf of the people.” In fact, Britain’s unelected House of Lords — often criticized as a relic of a vanished feudal aristocracy — has played a similar function, trying to limit the British government’s surveillance efforts and other new powers.

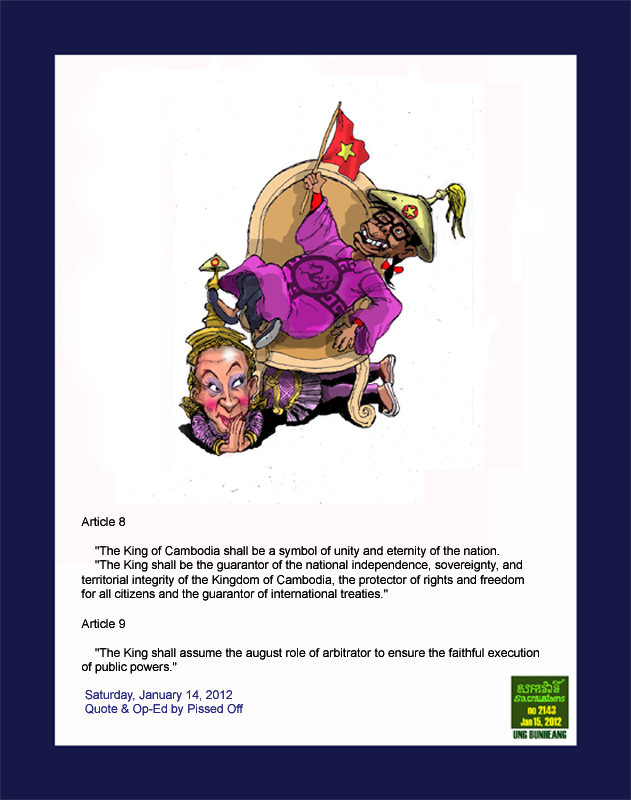

Similarly, in Cambodia former King Sihanouk (who has since stepped aside because of health reasons and now holds the title of King Father), frequently clashed with Prime Minister Hun Sen, who is elected but has amassed near-dictatorial powers in his office. Sihanouk frequently criticized Hun Sen’s strongman tactics, and invoked the royal institution as the protector of average people abused by the prime minister.

Monarchs, however, must walk a very fine line. Because today’s constitutional monarchs’ power is so nebulous, to use it effectively they must be extremely careful in wielding it.

In Thailand, King Bhumibol Adulyadej frequently has used public speeches to criticize what he sees as politicians who are too venal or power-hungry — which sometimes has veered into a political alignment with Bangkok-oriented elite parties and against parties aligned with rural people, who came to Bangkok and eventually led the demonstrations that resulted in violence. “The palace is thus very much in politics, although the general myth is that the king is above politics,” says Irene Stengs, an expert on the Thai monarchy at the Meertens Institute in the Netherlands.

In fact, the king sanctioned the 2006 coup, after it happened, that deposed populist former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra. With these actions, Bhumibol — who is protected from public criticism by strict lese majeste laws — has chipped away some of the respect he earned over decades. Among the “red shirts” battling the government, one has begun to hear anti-monarchical sentiments, though they are careful not to disdain the current monarch. In contrast to many previous rallies in Bangkok, the red shirts did not hold up noticeable photos of the king this time — interpreted as a sign of distrust of the palace.

Nepal’s royal family recently learned of the devastating consequences when a king overtly takes sides. After a Maoist insurgency rooted in the rural regions challenged Nepal’s parliamentary government in the late 1990s and early 2000s, then-King Gyanendra in 2005 took control of the government himself and attempted to dominate the security forces and to wipe out the Maoist movement. The suppression failed, even parliament turned against the crown, and the Maoists eventually took power in Kathmandu as part of a power-sharing agreement. In 2008, with Gyanendra’s reputation in tatters, Nepal created a republic and abolished the monarch, and Gyanendra moved out of his palace like a delinquent tenant.

For now, most of the other constitutional monarchies seem to have absorbed the lessons of places like Nepal. In Spain, Juan Carlos, though given an extremely conservative education and hailing from a conservative background, has worked with politicians from across the ideological spectrum. In Britain, even as the Labor, Conservative, and Liberal Democrat parties haggled with one another about forming a new government, Queen Elizabeth did not appear in public to bless any of their leaders — although she personally, according to Britain’s Daily Telegraph, disdained the Labor policies of Tony Blair. And according to British tradition, when the new Parliament convenes for the first time and the government formally announces its agenda for the year, the person who reads the speech — as she always does, no matter who is setting the policies — will be the Queen.

Joshua Kurlantzick is Fellow for Southeast Asia at the Council on Foreign Relations. He can be reached at jkurlantzick@cfr.org.