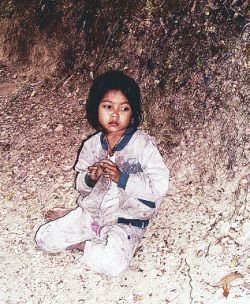

It is really sad to see such young children begging. This young girl did not even smile when given some “goodies''. (Photo Malaysia Star)

It is really sad to see such young children begging. This young girl did not even smile when given some “goodies''. (Photo Malaysia Star)Saturday April 1, 2006

BY C. K. TOH

The Star (Malaysia)

CAMBODIA’s Siem Reap seems to be “in” for the inveterate traveller these days, the main attraction being the temples of Angkor.

For decades, it was unsafe to visit. Civil wars, genocides, and landmines kept the tourists at bay. In the year 2000, things stabilised enough in the country for tourism to flourish and now the hotel industry is booming. There are some 200 hotels and guesthouses in Cambodia presently. Many of these are luxury establishments, which very few of the locals can afford for even a night.

Even more depressing is the sight of so many amputees due to the landmines during the wars and even now. Cambodians seem reserved, but once you start talking to them, they are a very friendly lot. Children don’t fare very well here. Inadequate medical care, poor hygiene and diseases have resulted in high mortality rates in children.

The infant mortality rate in 2003 was estimated to be 73.67 per 1,000 live births. This is in stark contrast to the situation in Malaysia at 7.9 per 1,000 live births. War and diseases like AIDS have also resulted in very high numbers of orphans. Poverty stricken families sometimes abandon or sell their children. Some children run away and live on the streets.

These street children organise themselves into gangs. In 2003, there were about 1,800 street children in Phnom Penh alone, and many of them were on drugs. These urchins are everywhere, on the streets, at tourist sites hawking tacky stuff, engaged in petty crimes and beggary and waiting for handouts. Cambodia has also acquired a reputation for child sex.

For most, school is a luxury. But there is hope for the future, with the government affirming commitment to compulsory education for all. Various charities and countries have also helped out by setting up schools and providing equipment.

By and large, the children are an impish lot and I enjoyed talking to them. Some are very bright, and most are always polite and graceful. A few can converse fairly well in English and a smattering of other languages. I will always remember the sprightly young girl in Angkor Thom. I was chatting with her and I asked, “Do you go to school?”

She replied, “See this blouse, see this skirt. My school uniform. I go to school in the morning and work here till night.”

Oops, my error, I did not recognise the soiled clothes she was wearing. When I asked her about homework, I drew a blank. Her companion, a cheerful little girl, gave a most delightful curtsy when given sweets and a ball pen.

The plight of these children have caught the attention of visitors to Cambodia. There are many charities, big and small, and individuals who provide help, from free medical care and schools to centres that help with skills training.

Among the more notable ones are the children's hospitals set up by Dr. Beat Richner, a Swiss pediatrician. There are three hospitals set up by him, two in Phnom Penh and one in Siem Reap, the Jayavarman VII Hospital. They treat about 42,000 inpatients and about half a million outpatients yearly.

The Angkor Hospital for Children doubles as a training hospital for young Cambodian doctors and nurses. This hospital, which has treated 265,000 children over six years, is managed by the Friends Without Borders. This foundation was set up Kenro Izu, a Japanese photographer who was moved by the plight of the children.

Krousar Thmey, (Khmer for New Family), an NGO funded by the European Union, provides help to rehabilitate street children, provides education for the underprivileged and handicapped and also to promote Khymer culture.

They have about 1,000 children under their direct care and provide support for another 3,000. Colors of Cambodia has an art gallery in Siem Reap. Paintings by children are sold and all proceeds go towards furthering the art education of the underprivileged.

There are many other charities, too many to mention here. Perhaps, you too will be inspired to help.

For additional information:

Dr. Beat Richner website: http://www.beat-richner.ch/

Angkor Hospital: http://www.angkorhospital.org/

Friends without border: http://www.fwab.org/

Krousar Thmey: http://www.myfriend.org/krousar-thmey/e/index.html (in English), http://www.myfriend.org/krousar-thmey/index.html (in French)

Mith Samlanh: http://www.streetfriends.org/

For decades, it was unsafe to visit. Civil wars, genocides, and landmines kept the tourists at bay. In the year 2000, things stabilised enough in the country for tourism to flourish and now the hotel industry is booming. There are some 200 hotels and guesthouses in Cambodia presently. Many of these are luxury establishments, which very few of the locals can afford for even a night.

Even more depressing is the sight of so many amputees due to the landmines during the wars and even now. Cambodians seem reserved, but once you start talking to them, they are a very friendly lot. Children don’t fare very well here. Inadequate medical care, poor hygiene and diseases have resulted in high mortality rates in children.

The infant mortality rate in 2003 was estimated to be 73.67 per 1,000 live births. This is in stark contrast to the situation in Malaysia at 7.9 per 1,000 live births. War and diseases like AIDS have also resulted in very high numbers of orphans. Poverty stricken families sometimes abandon or sell their children. Some children run away and live on the streets.

These street children organise themselves into gangs. In 2003, there were about 1,800 street children in Phnom Penh alone, and many of them were on drugs. These urchins are everywhere, on the streets, at tourist sites hawking tacky stuff, engaged in petty crimes and beggary and waiting for handouts. Cambodia has also acquired a reputation for child sex.

For most, school is a luxury. But there is hope for the future, with the government affirming commitment to compulsory education for all. Various charities and countries have also helped out by setting up schools and providing equipment.

By and large, the children are an impish lot and I enjoyed talking to them. Some are very bright, and most are always polite and graceful. A few can converse fairly well in English and a smattering of other languages. I will always remember the sprightly young girl in Angkor Thom. I was chatting with her and I asked, “Do you go to school?”

She replied, “See this blouse, see this skirt. My school uniform. I go to school in the morning and work here till night.”

Oops, my error, I did not recognise the soiled clothes she was wearing. When I asked her about homework, I drew a blank. Her companion, a cheerful little girl, gave a most delightful curtsy when given sweets and a ball pen.

The plight of these children have caught the attention of visitors to Cambodia. There are many charities, big and small, and individuals who provide help, from free medical care and schools to centres that help with skills training.

Among the more notable ones are the children's hospitals set up by Dr. Beat Richner, a Swiss pediatrician. There are three hospitals set up by him, two in Phnom Penh and one in Siem Reap, the Jayavarman VII Hospital. They treat about 42,000 inpatients and about half a million outpatients yearly.

The Angkor Hospital for Children doubles as a training hospital for young Cambodian doctors and nurses. This hospital, which has treated 265,000 children over six years, is managed by the Friends Without Borders. This foundation was set up Kenro Izu, a Japanese photographer who was moved by the plight of the children.

Krousar Thmey, (Khmer for New Family), an NGO funded by the European Union, provides help to rehabilitate street children, provides education for the underprivileged and handicapped and also to promote Khymer culture.

They have about 1,000 children under their direct care and provide support for another 3,000. Colors of Cambodia has an art gallery in Siem Reap. Paintings by children are sold and all proceeds go towards furthering the art education of the underprivileged.

There are many other charities, too many to mention here. Perhaps, you too will be inspired to help.

For additional information:

Dr. Beat Richner website: http://www.beat-richner.ch/

Angkor Hospital: http://www.angkorhospital.org/

Friends without border: http://www.fwab.org/

Krousar Thmey: http://www.myfriend.org/krousar-thmey/e/index.html (in English), http://www.myfriend.org/krousar-thmey/index.html (in French)

Mith Samlanh: http://www.streetfriends.org/

1 comment:

mariolesn@hotmail.com

Location San Antonio, TX

Comment Dear Members of C-Hope:

I am writing to you about the three hospitals in Cambodia that Swiss pediatrician Dr.Beat Richner has headed since 1992. You may already know of Jayavarman VII Hospital with its maternity annex and Kantha Bopha Hospitals I and II in Phnom Penh. They are renowned as the only world-class hospitals in Cambodia that offer first-world health care free of charge to all children. Everything is free of charge (outpatient consultations, hospitalization, surgical operations, deliveries, transportation to the hospital, and all medicine because 95% of Cambodian families are too poor to pay.

Annually for the three hospitals combined, here are some results:

• 800,000 parents receive basic health and hygiene education

• 910,000 children receive outpatient treatment

• 100,000 healthy children are vaccinated

• 70,000 critically ill children are hospitalized. (85% of all hospitalized Cambodian children are hospitalized in Dr. Richner’s hospitals. Lacking hospitalization, 75% of these children would die. 50% of all in-patients have tuberculosis. The largest killers are tuberculosis, malaria and AIDS. The 4. 5 day average hospital stay costs only $226

• 16,000 children receive life-saving surgery

• 11,000 babies are delivered, thereby preventing AIDS &TB transmission during birth

In 1992, only 52 doctors survived in Cambodia. Since then, Dr. Richner has realized one of his most important goals: Over 2500 Cambodian doctors have been trained in cutting-edge western medicine at his hospitals. Today, all 1540 hospital professionals are Cambodian, except for Dr. Richner and a French microbiologist. And these three hospitals become the nation’s university hospitals and training centers for physicians, medical students, physiotherapists and nurses. Today, Kantha Bopha has become the highly respected model for the entire Southeast Asian region of how efficient corruption-free medical and humanitarian aid can be delivered in the areas of preventive and curative medicine as well as in long-term staff training and research.

Dr. Richner's hospitals run almost entirely on donations. Of the $17.5 million annual budget for the three hospitals, 83% comes from private donations by the Swiss people, many of them Swiss children. The Swiss government pays 16% and the Cambodian government provides 1%. As far as I can discover, no funds come from U.S. citizens or the U.S. government. Can Dr. Richner’s work truly be unknown in the United States?

Today, Dr. Richner faces a huge challenge. Dr. Richner recounts, “We had a serious blow at the end of 2004. During our thirteen year history, we had always received a flood of year-end donations. But the catastrophic tsunami diverted funds from us. Ouur contributions have slowed to a trickle. Today, our annual budget has a devastating 30 percent shortfall, amounting to US $1.5 million. Our payroll for three months is $1.5 million. This will lead to tragic consequences for the children of Cambodia. Dr. Richner is pleading for immediate donations of any amount. He reminds us all that each dollar we give helps to cure, to save lives, and to prevent disease.

Since I returned to my home in Texas, I am haunted daily by memories of Jayavarman VII Hospital’s waiting room, where I saw more than 1,000 desperate Cambodian mothers holding seriously ill children. I remember the overcrowded inpatient wards. Two children had to sleep in each bed. With intravenous drips attached to their limbs, many more children slept on floor mats in the halls.

Of the 200,000 Cambodians living in the US today, I understand that 57% live on incomes of less than $25,000. However, I also know that many small contributions would make a big difference. It must be possible for us to raise at least a little of the needed money from some of the Cambodians living here in the U.S.

I would like to correspond with you about C-Hope. I am interested in banding together with those individuals and and groups of Cambodians and Americans across the United States that might be interested in forming a sister foundation here in the U.S. to the Kantha Bopha Foundation in Switzerland so that we can help Dr. Richner in his work. I am attaching below a newspaper article that I have written so you can read more about Dr. Richner's work. I am also attaching a form for donations—it asks for more money than any of us may have individually, but the address at the bottom is useful for even a tiny donation donations. They do accept checks in U.S. currency. And maybe your association could stage a fund-raising event on Kantha Bopha’s behalf? In any event, I would like to talk with you about any possible ideas you may have for how to help Kantha Bopha is the future. May I hear from you soon?

Sincerely,

Nancy S. MARIOLES

In the steps of Schweitzer: Free Medical Care for Cambodia's Children

By Nancy Marioles, copyright 2004. All rights reserved.

Near the temples of Angkor Wat, cellist Beatocello Richner, the storied "Doctor Schweitzer of Cambodia," plays music by Bach. Dr. Richner uses his musical talent to raise money so he can treat Cambodia's gravely ill children. Elected "Swiss Man of the Year," 2005 marks the thirtieth year that Swiss cellist and pediatrician Richner ce has devoted to achieve what no international aid organization has been able to do in Cambodia: He has set up three corruption-free hospitals giving first-world health care in one of the poorest countries of Asia.

Dr. Richner's task is Herculean. One in eight children under the age of five die in Cambodia. The largest killers are tuberculosis, malaria and AIDS. In his three hospitals in Phnom Penh and Siem Reap, 70,000 critically ill children are hospitalized, 910,000 children receive outpatient treatment, 16,000 have life-saaving surgery, and 100,000 healthy children are vaccinated each year. The average hospital stay lasts 4.5 days and costs $226. Over 11,000 babies are delivered in a specialized maternity ward to prevent AIDS & tuberculosis transmission during birth

"My hospitals provide free medicine and free medical care for everybody," stresses Dr. Richner, "The families in Cambodia are simply too poor to even pay one dollar cash towards medical care. In contrast to my hospitals, if you arrive at other Cambodian hospitals, first, you have to pay 'baksheesh' or 'please' money to the entrance security guard. Then you have to pay at least $100 up-front before you can get any care in the hospital. The average Cambodian survives on less than a dollar a day. In order to try to save their child's life, desperate parents sell their ox and their little plot of land. The child often dies in the hospital anyhow. And the parents are ruined because they no longer have any way to farm."

The huge waiting rooms of the hospitals fills with over 3,000 mothers daily. They sit patiently on floor mats, holding desperately sick children. During hours of waiting for their children to be seen by doctors, over 800,000 parents annually receive basic health and hygiene education delivered by closed circuit televisions. Inside clean hospital rooms, two children lie on opposite ends of each bed. Dr. Richner is unhappy about the overcrowding but he does not want to turn children away. And he lacks funds to build extra rooms.

Dr. Richner has a current staff of over 1,540 Cambodians. Only one Occidental specialist works with him.As 57 year-old Dr. Richner walks through the hospital, he is a walking locomotive, talking passionately about the hospital's struggles.

"We have eliminated the corruption that is endemic in other Cambodian hospitals," explains Dr. Richner. "We pay our staff a realistic monthly wage. Our nurses receive $200-300 and doctors and surgeons $600-700. Typically, government doctors receive $20 a month, although it takes at least $260 a month for them to live in Phnom Penh, the capital."

"Stamping out corruption is very expensive," Dr. Richner admits. "But to this day we have had no drug thefts at the hospitals. No money is taken under the table from families in order to make a living. These underhanded practices are the norm in all other Cambodian hospitals, including those of giant overseas aid organisations."

Dr. Richner first came to Kanpha Botha Hospital as a Red Cross volunteer doctor in 1974. When the Khmer Rouge purged Phnom Penh in 1975, Richner caught the last evacuation plane. But for the next 16 years in Zurich, he continued to carry his key to Kantha Bopha hospital in his pocket.

Coming back as a tourist in 1991 to Cambodia, Dr. Richner returned to visited his old hospital. "The country and the hospital itself was a disaster. Medical care was so much worse than it was in 1975. There was no water, no waste disposal, no electricity in the hospital anymore. And if people wanted medical care, they had to pay huge sums. And they were much too poor to pay." Cambodia's King Norodom Sihanouk asked Richner if he could find a way to rebuild the children's hospital.

Dr. Richner has been blessed by Divine Providence and extraordinary serendipity and. On his return flight to Switzerland after his visit with Cambodia's king, Dr. Richner talked excitedly to the stranger seated next to him about his dream. "In order to cut costs," I told him that I just have to find a way to convince the Swiss medical firm Diethelm in Bangkok to give a big discount and send all the needed equipment from Thailand to Cambodia." Surprised, my neighbor said, "Stop! No problem! You will get everything you need. I am the president of Diethelm in Zurich."

Shortly thereafter, a world newspaper wanted to do a story on Richner, the renowned cellist. But he could not stop talking to the journalist about the desperate plight of Cambodia's children. So, the paper featured his dream to restore the hospital, kicking off the first fund-raising drive which netted $6 million in only a few months. Less than a year later, Kantha Bopha Hospital reopened.

Using his musical talent, pediatrician Richner developed his stage character as Beatocello, a musical clown. He received the nickname Beatocello when Swiss fans combined his first name "Beat" with "cello" to give his clown a name that rhymes. Beatocello performs his popular free one-man show every Friday Saturday night at his hospital for tourists in Siem Reap. In a dramatic blend of tragic-comic storyteller, Dr. Richner plays Bach and sings of the children in his own compositions: "Every day, Cambodia's children lie dying, and at their sides, their mothers are crying."

"This man is the closest to a saint that I will ever meet," a Japanese backpacker exclaims, tears in her eyes. Dr. Richner intersperses his musical comedy with pleas for donations of money and blood.

Dr. Richner depends on tourists to donate 250 pints of blood per month. "Cambodians are afraid to donate. They think it will drain their powers. And Cambodians have good reasons not to trust most hospitals" Dr. Richner stressed. "We have a desperate need for blood. Some locals donate but up to 7% of the blood we inspect every day tests HIV positive and up to 16% is positive for hepatitis. Babies delivered HIV positive at all Cambodian hospitals are sent to us for blood transfusions. A clean blood supply is vital. We spend over a million dollars a year to test the blood at our hospitals."

Not having much money to donate, I go to the hospital to give blood. The donation procedures at the hospital are sterile and professional. Afterwards, donors receive a souvenir T-shirt, a meal and a soda.

Dr. Richner's hospitals run solely on donations with an annual budget of $17 million, receiving 90% from private donations from the Swiss people. They get 12% from the Swiss Government and 3% from the Cambodian government. Richer is proud that only 5% of the total funds are used to run the infrastructure of the foundation in Switzerland. Independent auditing is done by Pricewaterhouse Coopers.

The award-winning documentary about Dr. Richner's work entitled "...and the Beat Goes on" was featured at the Santa Barbara International Film Festival in 1999. It has since been shown on television around the world. A new documentary about Kantha Bopha stars Gerard Depardieu is ’Argent ou Le Sang” (“Money or Blood”). It will air for the first time in the United States on the French satellite channel 5 on March 30, 2005.

Kantha Bopha has become a highly respected model for the entire Southeast Asian region of just how efficient direct medical and humanitarian aid can be in the areas of preventive and curative medicine as well as in research and in long-term staff training.

But Dr. Richner has drawn criticism for "raising the benchmark" for the practice of medicine in Cambodia. Some think he spends too much money modern diagnostic procedures, such as CAT scans and for medicines. Dr. Richner insures that the drugs used in his hospitals are pure by buying them only from a central pharmacy in Copenhagen authorized by UNICEF. The medicine is from the original manufacturers, not questionable Asian counterfeit medicine.

Dr. Richner has a long-standing conflict with the UN World Health Organization (WHO). "The WHO still recommends treatment of tuberculosis in Cambodia with a cheap drug that was outlawed in the West since the 1970s because it is ineffective and it has dangerous side effects. It is passive genocide of Cambodia`s children." WHO believes in providing ”poor medicine for poor people in poor countries.”

Dr. Richner passionately asserts, "It is the right of every child to get proper diagnosis and effective medicine. Everything else is a violation of universal human rights."

"WHO and UNICEF staff pursue appalling double standards" he adds. "The U.N. pays $340 a night for their consultants to stay at the Hotel Sofitel Royal Angkor next door to my hospital in Siem Reap. Compare that to the $226 total hospital cost for me to save the life of one in-patient for five days. They criticize me, saying I provide Rolls-Royce medical care to Cambodian children. But when their own children need to be hospitalized, they air-vac them straight to the best hospital in Bangkok."

Today, Dr. Richner is facing two of his biggest challenges. The wooden structure of Kanpha Bopha I Hospital, destroyed by termites, must be replaced before imminent collapse. $30 million must be raised to rebuild the hospital. The Swiss people have already donated $20 million. The official groundbreaking in July of 2004 signified the Cambodian nation’s hope that $10 million more can be raised to re-open this urgently necessary hospital. It will include a enlarged 450 bed in-patient unit, radiology laboratory with sonography, four operating theaters and an intensive care unit.

“We had a serious blow at the end of 2004. During our thirteen year history, we had always received a flood of year-end donations. But the catastrophic tsunami diverted funds from us. Ouur contributions have slowed to a trickle. Today, our annual budget has a devastating 30 percent shortfall, amounting to US $1.5 million. Our payroll for three months is $1.5 million. This will lead to tragic consequences for the children of Cambodia. Dr. Richner is pleading for immediate donations of any amount. He reminds us all that each dollar we give helps to cure, to save lives, and to prevent disease.

Cambodia's government spends only one dollar annually on each of its 11.2 million citizens for health care. In addition, 4 dollars come from NGOs, the United Nations and the World Bank.

Almost half of hospitalized children suffer from a form of tuberculosis. Cambodia has the second highest tuberculosis infection rate in the world, according to World Health Organization figures.

How to Help

Website: http://www.beat-richner.ch/

To donate Euros, Swiss Francs, or US Dollars, Send checks to:

Kantha Bopha Hospital Cambodia

c/o Intercontrol AG, Seefeldstr. 17

CH-8008 Zürich

SWITZERLAND

Dr. Beatocello Richner presents his free one-man show in Siem Reap, every Friday and Saturday at 7:15PM at Jayavarman VII Hospital. A famous local landmark, the hospital is located on the road to Angkor Wat in Siem Reap.

Sponsor’s Membership in the Foundation for Kantha Bopha Childrens Hospital of Dr. Beat Richner

Print form, fill out, put in an envelope and send to:

Gönnerverein Kinderspitäler Beat Richner

Büro Dr. iur. Christian Steinmann

Bär & Karrer

Brandschenkestrasse 90

Postfach 1548

8027 Zürich

SWITZERLAND

SURNAME, first name: ..............................

Road …......................................................

City ………………………………………………….

Postal code: ............................................

District, State, Province: ……………………….

COUNTRY: …………………………………………..

Parent or Guardian’s name (needed only for youth

membership): ..........................................

___ I would like to become a sustaining, sponsor with an annual payment of 600 SFR/US$ 515 / € 387 / ₤ 268 Great Britain.

___ I would like to become a sustaining, sponsor as a youth member with an annual payment of SFR/US$ 86, € 387 / ₤ 65 Great Britain.). I will receive a pin, imprinted with a sketch by Dr. Beat Richner.

___ I would like to give a youth membership as a gift to:

SURNAME, first name: ……........................

Road ….....................................................

City ………………………………………………….

Postal code: ............................................

District, State, Province: ……………………….

COUNTRY: …………………………………………..

Parent or Guardian’s name (needed only for youth

membership): ..........................................

Date: .......................................................

Signature: .................................................

Gönnerverein Kinderspital Beat Richner

Büro Dr. iur. Christian Steinmann

Bär & Karrer

Brandschenkestrasse 90

Postfach 1548

8027 Zürich

SWITZERLAND

Post a Comment