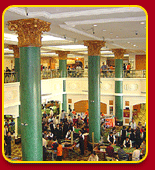

View inside the main hall and first floor of the Ho Wah Genting Casino in Poipet, one of the many gambing establishments benefiting mainly overseas investors and corrupt government officials, especially those in the top the government echelon. (Photo: Ho Wah Genting)

View inside the main hall and first floor of the Ho Wah Genting Casino in Poipet, one of the many gambing establishments benefiting mainly overseas investors and corrupt government officials, especially those in the top the government echelon. (Photo: Ho Wah Genting)BY YUSUKE MURAYAMA

THE ASAHI SHIMBUN

POIPET, Cambodia--The luxury casinos make for a sharp contrast with the humble bamboo and vinyl-sheeting houses of Kbal Spean village in Poipet near Cambodia's western border with Thailand.

It was a contrast that was brought home in deadly fashion last year.

On the morning of March 21, about 200 soldiers and militiamen armed with automatic rifles encircled the small village. They were there by court order to evict the residents.

The 220 or so families in the village emerged, armed with hatchets and kitchen knives, to stand up to the gunmen.

Then the sound of gunfire ripped through the silence.

"As soon as I heard a scream, those in front of me started shooting us," recalled Sim Chiv, 47, who was shot in the hip.

Another survivor, Sath Sun, 45, saw her 42-year-old husband shot to death while fleeing.

"He was shot in the right eyebrow," she said. "He had just come back from seasonal work."

In the end, the soldiers and militiamen killed five residents. They burned the village to the ground and cleared the debris with bulldozers.

Until 1997, nobody had even lived in the village. It used to be a minefield. But then several casinos set up shop. As their success took off, land prices in the area jumped.

One day a man calling himself the "village chief" appeared and claimed ownership of the land. Naturally, the residents disputed his claim.

Then the soldiers arrived.

In the aftermath of the tragedy, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights expressed concern, and the Cambodian government responded with an investigative committee.

Eventually, 130 soldiers and militiamen were indicted. In August, however, the Banteay Meanchey Court dismissed all charges against them.

"It is impossible to pinpoint who killed who during the incident," the court said.

So the residents did the only thing they could--they rebuilt their homes and went back to their daily lives. The truth of the attack remains unknown.

Heng Chantha, governor of Banteay Meanchey province, also serves as the local military commander. "The soldiers went there without my permission," he declares.

As for the so-called village chief, he has disappeared.

"The man who has disappeared is just a resident of the village," said a source. "A different person who is powerful enough to move the soldiers must have been behind him."

The source then referred to the name of a relative of a powerful politician.

One of the local casino operators who knows that politician's relative said the land grab is far from over.

"Such a big incident would not have occurred if there were no considerably powerful person" behind it, he says.

"I don't know if the relative has something to do with the incident. But the person is still trying to get the land."

It is hard to imagine that there would be such demand for a former minefield in western Cambodia. But Poipet is no longer nearly as poor as it used to be.

The area has seen rapid economic growth in recent years, mainly thanks to a booming casino industry that has been attracting hordes of Thais. There are now seven casinos, some with attached golf courses, along a 300-meter-long strip stretching from the national border to a checkpoint.

It appears that the casinos essentially operate outside the law.

"It has been decided that we are not authorized to investigate the casinos," said one local police officer. "The decision was made at a high level."

Although the seven casinos in Poipet alone are estimated to make the equivalent of several tens of billions of yen in pure profit annually, the total amount of taxes collected annually from all 19 casinos in Cambodia is only about 1 billion yen.

"Profits from casinos flow to politicians and high-ranking government officials who support the casino businesses from behind," said Son Chhay, 50, a lawmaker with the opposition Sam Rainsy Party.

"It is impossible to conduct investigations or tax collection appropriately."

In countries with proper tax collection, casinos are valuable financial resources. Macao generates a full 70 percent of its tax revenues from its casinos. In Malaysia, the conglomerate that monopolizes that country's casino industry pays as much as 20 billion yen in tax. In 2002, a state-run casino in the Philippines was that country's biggest corporate earner.

Casinos are also busy establishing their image as valuable contributors to society, and starting to make donations to various funds and local communities. But many people suspect that much of those donations goes to the supporters of ruling parties.

In South Korea, the government has allowed a state-run tourism firm to start a casino. How it uses those profits has turned into a huge issue at the national assembly.

The government says the company must give significant financial assistance to struggling sightseeing businesses at Mount Kumgang in North Korea. The opposition Democratic Party has accused the government of allowing the casino to open just so it could funnel money to the North Korean tourism industry.

The government now denies it is directly involved in how the casino uses its profits.

"The profits from the casino could be offered to the businesses in North Korea. But it is up to the corporation," said Suh Young Kil of South Korea's Ministry of Culture and Tourism.(IHT/Asahi: July 5,2006)

It was a contrast that was brought home in deadly fashion last year.

On the morning of March 21, about 200 soldiers and militiamen armed with automatic rifles encircled the small village. They were there by court order to evict the residents.

The 220 or so families in the village emerged, armed with hatchets and kitchen knives, to stand up to the gunmen.

Then the sound of gunfire ripped through the silence.

"As soon as I heard a scream, those in front of me started shooting us," recalled Sim Chiv, 47, who was shot in the hip.

Another survivor, Sath Sun, 45, saw her 42-year-old husband shot to death while fleeing.

"He was shot in the right eyebrow," she said. "He had just come back from seasonal work."

In the end, the soldiers and militiamen killed five residents. They burned the village to the ground and cleared the debris with bulldozers.

Until 1997, nobody had even lived in the village. It used to be a minefield. But then several casinos set up shop. As their success took off, land prices in the area jumped.

One day a man calling himself the "village chief" appeared and claimed ownership of the land. Naturally, the residents disputed his claim.

Then the soldiers arrived.

In the aftermath of the tragedy, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights expressed concern, and the Cambodian government responded with an investigative committee.

Eventually, 130 soldiers and militiamen were indicted. In August, however, the Banteay Meanchey Court dismissed all charges against them.

"It is impossible to pinpoint who killed who during the incident," the court said.

So the residents did the only thing they could--they rebuilt their homes and went back to their daily lives. The truth of the attack remains unknown.

Heng Chantha, governor of Banteay Meanchey province, also serves as the local military commander. "The soldiers went there without my permission," he declares.

As for the so-called village chief, he has disappeared.

"The man who has disappeared is just a resident of the village," said a source. "A different person who is powerful enough to move the soldiers must have been behind him."

The source then referred to the name of a relative of a powerful politician.

One of the local casino operators who knows that politician's relative said the land grab is far from over.

"Such a big incident would not have occurred if there were no considerably powerful person" behind it, he says.

"I don't know if the relative has something to do with the incident. But the person is still trying to get the land."

It is hard to imagine that there would be such demand for a former minefield in western Cambodia. But Poipet is no longer nearly as poor as it used to be.

The area has seen rapid economic growth in recent years, mainly thanks to a booming casino industry that has been attracting hordes of Thais. There are now seven casinos, some with attached golf courses, along a 300-meter-long strip stretching from the national border to a checkpoint.

It appears that the casinos essentially operate outside the law.

"It has been decided that we are not authorized to investigate the casinos," said one local police officer. "The decision was made at a high level."

Although the seven casinos in Poipet alone are estimated to make the equivalent of several tens of billions of yen in pure profit annually, the total amount of taxes collected annually from all 19 casinos in Cambodia is only about 1 billion yen.

"Profits from casinos flow to politicians and high-ranking government officials who support the casino businesses from behind," said Son Chhay, 50, a lawmaker with the opposition Sam Rainsy Party.

"It is impossible to conduct investigations or tax collection appropriately."

In countries with proper tax collection, casinos are valuable financial resources. Macao generates a full 70 percent of its tax revenues from its casinos. In Malaysia, the conglomerate that monopolizes that country's casino industry pays as much as 20 billion yen in tax. In 2002, a state-run casino in the Philippines was that country's biggest corporate earner.

Casinos are also busy establishing their image as valuable contributors to society, and starting to make donations to various funds and local communities. But many people suspect that much of those donations goes to the supporters of ruling parties.

In South Korea, the government has allowed a state-run tourism firm to start a casino. How it uses those profits has turned into a huge issue at the national assembly.

The government says the company must give significant financial assistance to struggling sightseeing businesses at Mount Kumgang in North Korea. The opposition Democratic Party has accused the government of allowing the casino to open just so it could funnel money to the North Korean tourism industry.

The government now denies it is directly involved in how the casino uses its profits.

"The profits from the casino could be offered to the businesses in North Korea. But it is up to the corporation," said Suh Young Kil of South Korea's Ministry of Culture and Tourism.(IHT/Asahi: July 5,2006)

3 comments:

as the sihanoukeville governor recently said after razing 71 homes for a hotel: it's all about "poverty reduction"

just burn that casino to the grown bro

i thought luxury casino is offen built in the rich country like US, or Brunei..why built in the poors country like Cambodai??...to suck the from the poors..for sure!!

Post a Comment