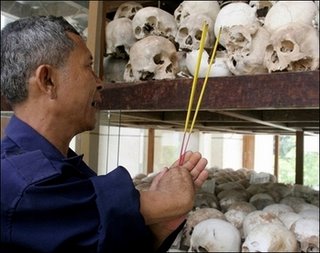

Chhorn Sok,49, holds incense as he offers prayers in front of the skulls displyed at the Choeung Ek killing fields memorial, southwest of Phnom Penh. Debate begins this week on internal rules to shape Cambodia's Khmer Rouge trials, but some fear the tribunal's efforts are being undermined by a misunderstanding of what the court seeks to do.(AFP/Tang Chhin Sothy)

Chhorn Sok,49, holds incense as he offers prayers in front of the skulls displyed at the Choeung Ek killing fields memorial, southwest of Phnom Penh. Debate begins this week on internal rules to shape Cambodia's Khmer Rouge trials, but some fear the tribunal's efforts are being undermined by a misunderstanding of what the court seeks to do.(AFP/Tang Chhin Sothy)By Seth Meixner

PHNOM PENH (AFP) - Debate begins this week on internal rules to shape Cambodia's Khmer Rouge trials, but some fear the tribunal's efforts are being undermined by a misunderstanding of what the court seeks to do.

Foreign judges Monday will begin discussing with their Cambodian counterparts the more than 100 tribunal regulations seeking to find common ground between varied legal codes.

The adoption of this procedural framework, expected at the end of the week, will take the tribunal a significant step forward, officials say.

"It's a road map for everybody. Without these rules the court cannot function properly," said tribunal spokesman Reach Sambath.

But the man who will prosecute one of the 20th century's worst genocides said the trial on which Cambodia has pinned so many of its hopes for reconciliation is misunderstood by those it is meant to serve.

"We haven't done a good job of telling people there is a mountain of evidence and about the way we get through it," Robert Petit, one of two tribunal co-prosecutors, said in an interview last week.

"Obviously there is a need for better information sharing," he said.

He said that not enough money or effort had been spent on outreach programs explaining the complex court procedure to the Cambodian public, putting the tribunal's credibility at risk.

"If the court isn't understood by the general public, it will fail," added co-investigating judge Marcel Lemonde, saying discussions were underway to organise monthly update briefings.

But lessons on dry legal procedure would likely be lost on many Cambodian villagers, who are concerned less about jurisprudence and more that "people are indicted and leaders arrested," said genocide researcher Youk Chhang.

"The public's expectations will be completely different than the court's delivery," Youk Chhang, director of the Documentation Center of Cambodia which has been compiling evidence against regime leaders, told AFP.

"The public expects the trial to begin soon. ... They don't care about how you handle a case. They want a final judgement," he added.

As many as 10 former Khmer Rouge leaders are expected to be called to the dock over the apocalypse that engulfed Cambodia in the late 1970s.

The communist regime turned the already war-battered country into a vast collective farm between 1975 and 1979 in its drive for an agrarian utopia, forcing millions into the countryside.

Up to two million people died of starvation, overwork and from executions during the four-year rule of the Khmer Rouge, which abolished religion, property rights, currency and schools.

Prosecutors in the three-year, joint UN-Cambodian tribunal are expected to hand up the names of potential defendants to an investigating judge by the end of the year.

Trials are expected to start in mid-2007, but Youk Chhang said there is a growing feeling among Cambodians that the tribunal is being done less for their benefit and more to raise the profile of its international backers.

"It is important right now that this process is accepted by the victims -- that they feel ownership," he said.

"If (tribunal staff) do their job and concentrate, meet their deadlines, it should be okay," he said.

Foreign judges Monday will begin discussing with their Cambodian counterparts the more than 100 tribunal regulations seeking to find common ground between varied legal codes.

The adoption of this procedural framework, expected at the end of the week, will take the tribunal a significant step forward, officials say.

"It's a road map for everybody. Without these rules the court cannot function properly," said tribunal spokesman Reach Sambath.

But the man who will prosecute one of the 20th century's worst genocides said the trial on which Cambodia has pinned so many of its hopes for reconciliation is misunderstood by those it is meant to serve.

"We haven't done a good job of telling people there is a mountain of evidence and about the way we get through it," Robert Petit, one of two tribunal co-prosecutors, said in an interview last week.

"Obviously there is a need for better information sharing," he said.

He said that not enough money or effort had been spent on outreach programs explaining the complex court procedure to the Cambodian public, putting the tribunal's credibility at risk.

"If the court isn't understood by the general public, it will fail," added co-investigating judge Marcel Lemonde, saying discussions were underway to organise monthly update briefings.

But lessons on dry legal procedure would likely be lost on many Cambodian villagers, who are concerned less about jurisprudence and more that "people are indicted and leaders arrested," said genocide researcher Youk Chhang.

"The public's expectations will be completely different than the court's delivery," Youk Chhang, director of the Documentation Center of Cambodia which has been compiling evidence against regime leaders, told AFP.

"The public expects the trial to begin soon. ... They don't care about how you handle a case. They want a final judgement," he added.

As many as 10 former Khmer Rouge leaders are expected to be called to the dock over the apocalypse that engulfed Cambodia in the late 1970s.

The communist regime turned the already war-battered country into a vast collective farm between 1975 and 1979 in its drive for an agrarian utopia, forcing millions into the countryside.

Up to two million people died of starvation, overwork and from executions during the four-year rule of the Khmer Rouge, which abolished religion, property rights, currency and schools.

Prosecutors in the three-year, joint UN-Cambodian tribunal are expected to hand up the names of potential defendants to an investigating judge by the end of the year.

Trials are expected to start in mid-2007, but Youk Chhang said there is a growing feeling among Cambodians that the tribunal is being done less for their benefit and more to raise the profile of its international backers.

"It is important right now that this process is accepted by the victims -- that they feel ownership," he said.

"If (tribunal staff) do their job and concentrate, meet their deadlines, it should be okay," he said.

1 comment:

Why international community spent time and money to trial Khmer rouge? Why need to find justice? When these Khmer rouge killed innocent Cambodian people, do they have court to trial before killing them? The answer is NO. So just send Interpol police or secret police to catch and execute them all including Sihanouk. These people are criminal.

These trial dragged for years because of Hun Sen government and Sihanouk tried to block the trial. They do whatever they can to delay these trial.

So sick to hear and read the article.

Post a Comment