by Martin Rathie (Guest Contributor)

New Mandala

[Martin Rathie is a PhD scholar formerly with the Department of History at the University of Queensland. Currently based in the Lao capital, Martin works as a teacher at Vientiane College.]

In his final days while under house arrest in Anlong Veng, Pol Pot brought attention to a little known Cambodian Communist called Ya, by accusing him of being the ringleader of the traitorous forces that led to the demise of Democratic Kampuchea. For the last few years I have been unearthing the links between the Lao and Cambodian revolutionary movements. I have been investigating the contacts between revolutionaries in southern Laos, northern Cambodia and northeastern Thailand. My focus has been the relationship between the Pathet Lao and the Khmer Rouge. However, the scope of this study has spilled over to Isan as the two revolutionary movements struggled for influence over the ethnic Lao and Khmer Communists of northeastern Thailand; specifically the Isan Tai branch of the Communist Party of Thailand. My research covers the southern command of the Pathet Lao, Isan-Lao revolutionary relations, provincial historical studies, tributary relations, patron-client networks, relations amongst anti-Vietnamese forces in the Lao-Cambodian frontier region, cross-border migrations and trade, and the mysterious origins of the Communist networks in Stung Treng, Ratanakiri and Preah Vihear.

I have visited Anlong Veng twice this year (January and October) to interview Khmer Rouge (KR) veterans who originated from northeastern Cambodia. Many of them are Khmer Leu (upland Cambodians, mostly speakers of Austroasiatic languages) or ethnic Lao. My interest is to show that the KR didn’t treat the ethnic Lao particularly harshly during their reign, i.e. there wasn’t an aggressive racial stance against the Lao of northeastern Cambodia. Certainly there were abuses and the killing of ethnic Lao, but it is interesting to see how many gained positions of influence during Democratic Kampuchea and following the Vietnamese occupation. In addition, it has been surprising to learn that a number of wives of purged officials from the northeast did survive, as did their children. For example the chief of Stung Treng (known as Sector 104 by the KR), an ethnic Khmer called But, was purged for contacts with the Lao as tensions rose between Vietnam and Cambodia in 1978. However, his wife is alive and well in western Cambodia. From previous readings from the works of David Chandler and Ben Kiernan it seemed that Angkar Leu (the Upper Organization of the Communist Party of Kampuchea) was ruthless in purging all relatives and associates of party enemies, but not necessarily so. Another interesting example is the case of Laing, the chief of Mondulkiri (known as Sector 105 by the KR), who was associated through marriage and work with the “super traitor”, Ta Ya. If you recall, Ya was the figure mentioned by Pol Pot in his final interview with Nate Thayer for conspiring with the Vietnamese against Angkar.

Ya was the final revolutionary name used by the veteran Cambodian Communist Ney Sarann. Ney Sarann, a Sino-Khmer, originated from Svay Rieng province where he joined the Indochinese Communist Party along with Sao Pheum (later Democratic Kampuchea’s Eastern Zone commander) and Keo Meas in the late 1940s. He trained in the Central Highlands of Vietnam during the First Indochina War and served as a liaison for the Khmer People’s Revolutionary Party’s little known northeastern cell, which was administered by Seda and his deputy Ya Kon (ethnic Lao) based in Voeunsai, Ratanakiri.

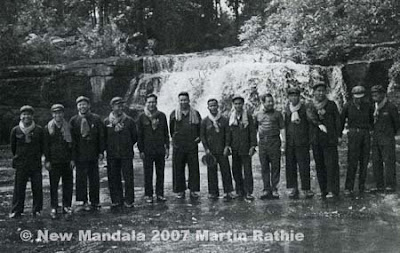

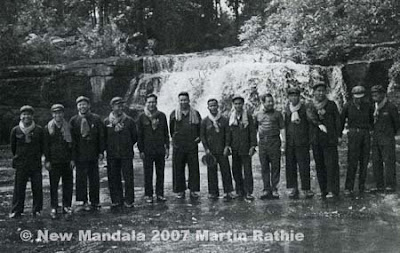

Ney Sarann (third from right) at Phnom Kulen. (An image from a Chinese-produced booklet.) The photo shows from left to right: Koy Thuon (Northern Zone commander), Khieu Samphan, Ieng Sary, Hu Nim, Hou Yuon, Pol Pot, then two unknown cadres, Sihanouk, unknown guard, Ney Sarann (Ya), unknown cadres.

Ney Sarann (third from right) at Phnom Kulen. (An image from a Chinese-produced booklet.) The photo shows from left to right: Koy Thuon (Northern Zone commander), Khieu Samphan, Ieng Sary, Hu Nim, Hou Yuon, Pol Pot, then two unknown cadres, Sihanouk, unknown guard, Ney Sarann (Ya), unknown cadres.

Seda was the first regional secretary for the KPRP in northeastern Cambodia. For a long time it was believed that the Cambodian Communists didn’t have a branch in the northeast until the arrival of Ieng Sary and Son Sen in the early 1960s, but it was active under Seda since the late 1940s. The interesting point to note is that this branch of the KPRP was dominated by ethnic Lao. Chan Daeng was another ethnic Lao who worked with Seda. He studied in northern Vietnam after 1954. His wife Borkai is still alive and living in Stung Treng. Thongsy (as mentioned by Philip Short, but studied by me) was an ethnic Lao native of Voeunsai. Chan Nukeo, a native of Lumphat, was another ethnic Lao who worked with the KR.

I have interviewed ethnic Lao, Brao, Kravet, Kreung, Jarai and Khmer from Stung Treng and Ratanakiri who give differing accounts of Seda. Most of them agree he was active between Siempang and Voeunsai, and traveled to other parts of the northeast. Some said Seda came from Chantuk which is the village between these settlements. For me this is an interesting point because the French drafted locals to build a landlink between Siempang and Voeunsai which was resented as a pointless endeavour in the eyes of locals, who knew the wet season would quickly erode/disable any road built through the wilderness. In addition, the French brought in Vietnamese coolies to help with public works. My theory is that Indochinese Communist Party (ICP) sympathizers/agents in the public works probably recruited locals while working on the transport links and border demarcation projects. This is how the ICP successfully recruited Lao in Savannakhet and Khammuan.

Some northeasters said Seda was Khmer and could speak Lao and other ethnic languages fluently. Others said he was Lao and could speak Khmer well. Many said he was Khmer Voeunsai which is commonly understood to mean Lao, as most people in Voeunsai are ethnic Lao or Chinese. Seda is a Khmer botanic term and there is a village near Lumphat with this name. However, it could also be a Lao name, but generally spelt as Sida. The ICP had a cell in Voeunsai which was overseen by Seda and Ya Kon (short for Phraya Virakorn). Ya Kon’s grandfather, Chao Khamphouy, was the Lao noble who founded Voeunsai in the 19th century. At that time it was tributary to Champasak and important cultural and economic exchanges passed between the two. Chao Khamphouy served as the governor of Mounlapomok, the area covering northern Ratanakiri, during the French period. An interesting side note is that Ya Kon was the father of the Lao People’s Revolutionary Party Politburo member Osakanh Thammatheva. In the early 1950s Osakanh was sent by his father for political training in northern Vietnam while other ethnic Lao and Khmer Leu from Ratanakiri, such as Thongdam Chanthaphomma , were sent for military training. Osakanh joined the Pathet Lao, married a lady from Sam Neua and became an important military cadre in northern Laos. Thongdam, a Voeunsai native, joined the Pathet Lao and later became governor of Attapeu province after 1975.

In the early days of the Cambodian Communist movement, the northeastern revolutionaries had much more in common with the Viet Minh in the Central Highlands (in the region known as LKV) and the Pathet Lao in southern Laos (then based in Ban Hinlat, Sanamxai district, Attapeu) than with its own leadership in Phnom Penh. Ieng Sary has mentioned a cadre called Thongsy (in Philip Short’s book) as a leading figure for the KR in the northeast of Cambodia. It seems that the ICP/KPRP generation of Cambodian Communists was succeeded in the early 1960s by the KR, when Seda and Ya Kon were liquidated by Sihanouk’s forces following the defection of Siev Haeng in 1959. Ya Kon was killed by government forces in Lumphat.

After the 1954 Geneva Accords Ney Sarann participated in Cambodian politics as a member of the Krom Pracheachon (the Khmer People’s Revolutionary Party’s legal front), and ran as a candidate in national elections for his home province. At the same time Ney Sarann worked as a teacher and educational administrator for the private schools in Phnom Penh (details of Ya’s actual education are sketchy). During the early Sangkum period Ney Sarann served as Saloth Sar’s supervisor at the Chamroan Vichea School. From most accounts Ney Sarann was a popular teacher like Saloth Sar and played an important role in recruiting monks and students into the Communist movement. However, it is not known how active he was outside of the capital during 1955-1963. With the withdrawal of Saloth Sar from Phnom Penh to the Viet-Cambodian frontier in the early 1960s, Ney Sarann was reassigned to work in Mondulkiri. For Lao-Cambodian relations this was an important step, as Ney Sarann married a local lady of Lao ethnicity named Voeun and developed close relations with the local people, be they ethnic Tampuan, Pnong, Kuy, Jarai, Brao or Lao.

The ethnic Lao of Mondulkiri, largely centred on the district of Kaoh Nhek, had important networks with Lao in Stung Treng, Lumphat, Voeunsai, Siempang and of course Laos. Ney Sarann was able to tap into these and rapidly develop the revolutionary movement in the northeast. This was because the ethnic Lao had historically been the most efficient networkers in the region, due to their trade in forest goods and Buddhist missionary activities. Thus allowing them to successfully integrate with the local peoples and gain their trust. During the late 1960s and early 1970s Ney Sarann moved around northeastern Cambodia and Preah Vihear province recruiting people into the KR. In addition, he played an important role as liaison with the Vietnamese and Lao when receiving military supplies down the Sihanouk Trail (note this refers to the northern branch which comes off the Ho Chi Minh Trail in eastern Attapeu province and follows the Xekong valley into Stung Treng province). Khmer Leu and ethnic Lao people from the northeast commented that Ney Sarann’s leadership at the local level was fair and pragmatic, although he was definitely linked to revenge killings of Lon Nol regime figures. In 1973 Ney Sarann received Sihanouk at the Lao-Cambodian frontier with Khieu Samphan and Hou Yuon, after the exiled prince had traveled down the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Ney Sarann and Bou Phat (chief of Preah Vihear province, then known as Sector 103 by the KR) escorted Sihanouk and his Chinese entourage from Veunkham (Lao border crossing point in southern Champasak province) to Phnom Kulen (Siem Reap province) and back.

Before the fall of Phnom Penh, Ney Sarann was moved from the northeast to the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) headquarters in central Cambodia, where it is understood that he took charge of military logistics before the final seizure of the capital. After April 17 Ney Sarann served in Phnom Penh and joined a Democratic Kampuchea (DK) delegation seeking material support from China. The removal of Ney Sarann from northeastern Cambodia in 1973/74 resulted in a breakdown of local support in the KR as new lowland cadres, such as Son Sen’s brother Nikan, enforced CPK policy more strictly on the indigenous community and overtly criticized the Vietnamese as evil parasites. This resulted in groups of Khmer Leu and ethnic Lao, led by figures such as Bou Thong (Tampuan), Seuy Keo (Kachok), Bun Mi (Brao) and Nou Beng (Lao), fleeing to Vietnam and Laos. They later became the new leaders of the People’s Republic of Kampuchea (PRK) due to their privileged status with the Vietnamese, which was cultivated during their time in exile. Bou Thong became Defence Minister in the PRK and Seuy Keo his deputy. Nou Beng became the PRK’s Health Minister, but feel from grace after being caught trafficking opium. Bun Mi was also chosen for high office in the PRK, but he feel chronically ill and insane after receiving bad anesthesia during an operation to remove a bullet from his shoulder.

At this point, early 1976, Angkar Leu reassigned Ney Sarann to the northeast, so as to bring order to the region. In addition, Ney Sarann administered a larger territory which covered Stung Treng, Ratanakiri, Mondulkiri and Kracheh. The embarrassment of the Khmer Leu refugees was complicated by border tensions between Vietnam and Cambodia, which had been simmering since Khmer and Vietnamese forces had snatched island territories from each other in early 1975 and argued over the exploitation of maritime resources. Being an elder brother of the party and fluent in Vietnamese, Ney Sarann was appointed a negotiator in the DK-Socialist Republic of Vietnam border dispute, which extended up into the highland district of O Yadav, Ratanakiri. Around this period, early 1976, suspicions were fermenting inside Angkar Leu as the party leadership felt threatened by ‘hidden rivals’ and Ney Sarann, then commonly known as Ta Ya, became a target of investigation.

It is known that Ya had long-standing differences of opinion with Pol Pot with regards to economic management, but whether he actively conspired against him remains unclear. Certainly he was aligned with CPK moderates such as Koy Thuon (former chief of the KR’s Northern Zone and then DK Economics and Trade Minister) and Hou Yuon, which placed him in dangerous company. Nevertheless it cannot be doubted that Ney Sarann was a party loyalist as he actively pursued the party’s interests in border negotiations. By late 1976 it had been decided by Angkar Leu that Ya was a traitor due to his association with the Vietnamese and other party ‘revisionists’ also accused of plotting to topple the regime. This resulted in his arrest in September and imprisonment at Toul Sleng, where he was questioned and tortured brutally. Subsequently, a large number of cadres from the northeast and elsewhere were purged for being members of Ya’s “Laos Plot” (this term appears in other “confessions” and relates to a revisionist faction in the CPK seeking to adopt a moderate form of socialist construction as employed by the Pathet Lao).

An interesting development from this tragic series of events was that relatives of Ya in Mondulkiri survived the party crackdown and remained faithful to Angkar Leu right up until the 1990s. Ya’s in-laws Laing (secretary of Mondulkiri) and Khamphoun (deputy secretary), who took charge of Sector 105 in the 1970s, died at the hands of each other rather than the guards of S-21 at Toul Sleng prison (A detailed study of their activities by Sara Colm and Sorya Sim is being released soon by the Documentation Centre of Cambodia). Laing’s brothers Lork and Onsi, both ethnic Lao, joined the Sector’s administrative committee in 1978 and in 1986 led hundreds of KR followers from the northeast to the Dangrek Range, where they entered the service of Ta Mok, Son Sen and Ke Pauk. Onsi who served alongside Nhem San (former commander of Division 920 and Son Sen’s killer) now lives in Anlong Veng town, a short distance from Ke Pauk’s children and the S-21 photographer Nhem En, and spends his time gardening like many KR veterans. Mrs. Bua Channa, the niece of Ney Sarann, is now the women’s affairs official for Phum 105, the village where many Khmer Leu associated with the KR leadership are now based. Her husband, Koy Tuan, the former personal assistant to So Sareuan (protégé of Pol Pot and Son Sen’s killer) is also a sub-district official. All of these veterans are firmly settled in Otdar Meanchey province, but maintain their Lao and Khmer Leu culture. Phum 105 sits at the base of the Dangrek escarpment below Pol Pot’s now derelict bunker. It is an unusually tidy village in a picturesque setting, receiving support from a collection of NGOs. This is a sharp contrast to the squalor that surrounds the graves of Pol Pot and Ta Mok, located to the northwest of Phum 105. Some 5-10 kilometers away from the main road linking Anlong Veng with Chong Sa-ngam pass, Phum 105 enjoys a surprising level of harmony in an area where conflict dominated daily life for so long.

In his final days while under house arrest in Anlong Veng, Pol Pot brought attention to a little known Cambodian Communist called Ya, by accusing him of being the ringleader of the traitorous forces that led to the demise of Democratic Kampuchea. For the last few years I have been unearthing the links between the Lao and Cambodian revolutionary movements. I have been investigating the contacts between revolutionaries in southern Laos, northern Cambodia and northeastern Thailand. My focus has been the relationship between the Pathet Lao and the Khmer Rouge. However, the scope of this study has spilled over to Isan as the two revolutionary movements struggled for influence over the ethnic Lao and Khmer Communists of northeastern Thailand; specifically the Isan Tai branch of the Communist Party of Thailand. My research covers the southern command of the Pathet Lao, Isan-Lao revolutionary relations, provincial historical studies, tributary relations, patron-client networks, relations amongst anti-Vietnamese forces in the Lao-Cambodian frontier region, cross-border migrations and trade, and the mysterious origins of the Communist networks in Stung Treng, Ratanakiri and Preah Vihear.

I have visited Anlong Veng twice this year (January and October) to interview Khmer Rouge (KR) veterans who originated from northeastern Cambodia. Many of them are Khmer Leu (upland Cambodians, mostly speakers of Austroasiatic languages) or ethnic Lao. My interest is to show that the KR didn’t treat the ethnic Lao particularly harshly during their reign, i.e. there wasn’t an aggressive racial stance against the Lao of northeastern Cambodia. Certainly there were abuses and the killing of ethnic Lao, but it is interesting to see how many gained positions of influence during Democratic Kampuchea and following the Vietnamese occupation. In addition, it has been surprising to learn that a number of wives of purged officials from the northeast did survive, as did their children. For example the chief of Stung Treng (known as Sector 104 by the KR), an ethnic Khmer called But, was purged for contacts with the Lao as tensions rose between Vietnam and Cambodia in 1978. However, his wife is alive and well in western Cambodia. From previous readings from the works of David Chandler and Ben Kiernan it seemed that Angkar Leu (the Upper Organization of the Communist Party of Kampuchea) was ruthless in purging all relatives and associates of party enemies, but not necessarily so. Another interesting example is the case of Laing, the chief of Mondulkiri (known as Sector 105 by the KR), who was associated through marriage and work with the “super traitor”, Ta Ya. If you recall, Ya was the figure mentioned by Pol Pot in his final interview with Nate Thayer for conspiring with the Vietnamese against Angkar.

Ya was the final revolutionary name used by the veteran Cambodian Communist Ney Sarann. Ney Sarann, a Sino-Khmer, originated from Svay Rieng province where he joined the Indochinese Communist Party along with Sao Pheum (later Democratic Kampuchea’s Eastern Zone commander) and Keo Meas in the late 1940s. He trained in the Central Highlands of Vietnam during the First Indochina War and served as a liaison for the Khmer People’s Revolutionary Party’s little known northeastern cell, which was administered by Seda and his deputy Ya Kon (ethnic Lao) based in Voeunsai, Ratanakiri.

Ney Sarann (third from right) at Phnom Kulen. (An image from a Chinese-produced booklet.) The photo shows from left to right: Koy Thuon (Northern Zone commander), Khieu Samphan, Ieng Sary, Hu Nim, Hou Yuon, Pol Pot, then two unknown cadres, Sihanouk, unknown guard, Ney Sarann (Ya), unknown cadres.

Ney Sarann (third from right) at Phnom Kulen. (An image from a Chinese-produced booklet.) The photo shows from left to right: Koy Thuon (Northern Zone commander), Khieu Samphan, Ieng Sary, Hu Nim, Hou Yuon, Pol Pot, then two unknown cadres, Sihanouk, unknown guard, Ney Sarann (Ya), unknown cadres.Seda was the first regional secretary for the KPRP in northeastern Cambodia. For a long time it was believed that the Cambodian Communists didn’t have a branch in the northeast until the arrival of Ieng Sary and Son Sen in the early 1960s, but it was active under Seda since the late 1940s. The interesting point to note is that this branch of the KPRP was dominated by ethnic Lao. Chan Daeng was another ethnic Lao who worked with Seda. He studied in northern Vietnam after 1954. His wife Borkai is still alive and living in Stung Treng. Thongsy (as mentioned by Philip Short, but studied by me) was an ethnic Lao native of Voeunsai. Chan Nukeo, a native of Lumphat, was another ethnic Lao who worked with the KR.

I have interviewed ethnic Lao, Brao, Kravet, Kreung, Jarai and Khmer from Stung Treng and Ratanakiri who give differing accounts of Seda. Most of them agree he was active between Siempang and Voeunsai, and traveled to other parts of the northeast. Some said Seda came from Chantuk which is the village between these settlements. For me this is an interesting point because the French drafted locals to build a landlink between Siempang and Voeunsai which was resented as a pointless endeavour in the eyes of locals, who knew the wet season would quickly erode/disable any road built through the wilderness. In addition, the French brought in Vietnamese coolies to help with public works. My theory is that Indochinese Communist Party (ICP) sympathizers/agents in the public works probably recruited locals while working on the transport links and border demarcation projects. This is how the ICP successfully recruited Lao in Savannakhet and Khammuan.

Some northeasters said Seda was Khmer and could speak Lao and other ethnic languages fluently. Others said he was Lao and could speak Khmer well. Many said he was Khmer Voeunsai which is commonly understood to mean Lao, as most people in Voeunsai are ethnic Lao or Chinese. Seda is a Khmer botanic term and there is a village near Lumphat with this name. However, it could also be a Lao name, but generally spelt as Sida. The ICP had a cell in Voeunsai which was overseen by Seda and Ya Kon (short for Phraya Virakorn). Ya Kon’s grandfather, Chao Khamphouy, was the Lao noble who founded Voeunsai in the 19th century. At that time it was tributary to Champasak and important cultural and economic exchanges passed between the two. Chao Khamphouy served as the governor of Mounlapomok, the area covering northern Ratanakiri, during the French period. An interesting side note is that Ya Kon was the father of the Lao People’s Revolutionary Party Politburo member Osakanh Thammatheva. In the early 1950s Osakanh was sent by his father for political training in northern Vietnam while other ethnic Lao and Khmer Leu from Ratanakiri, such as Thongdam Chanthaphomma , were sent for military training. Osakanh joined the Pathet Lao, married a lady from Sam Neua and became an important military cadre in northern Laos. Thongdam, a Voeunsai native, joined the Pathet Lao and later became governor of Attapeu province after 1975.

In the early days of the Cambodian Communist movement, the northeastern revolutionaries had much more in common with the Viet Minh in the Central Highlands (in the region known as LKV) and the Pathet Lao in southern Laos (then based in Ban Hinlat, Sanamxai district, Attapeu) than with its own leadership in Phnom Penh. Ieng Sary has mentioned a cadre called Thongsy (in Philip Short’s book) as a leading figure for the KR in the northeast of Cambodia. It seems that the ICP/KPRP generation of Cambodian Communists was succeeded in the early 1960s by the KR, when Seda and Ya Kon were liquidated by Sihanouk’s forces following the defection of Siev Haeng in 1959. Ya Kon was killed by government forces in Lumphat.

After the 1954 Geneva Accords Ney Sarann participated in Cambodian politics as a member of the Krom Pracheachon (the Khmer People’s Revolutionary Party’s legal front), and ran as a candidate in national elections for his home province. At the same time Ney Sarann worked as a teacher and educational administrator for the private schools in Phnom Penh (details of Ya’s actual education are sketchy). During the early Sangkum period Ney Sarann served as Saloth Sar’s supervisor at the Chamroan Vichea School. From most accounts Ney Sarann was a popular teacher like Saloth Sar and played an important role in recruiting monks and students into the Communist movement. However, it is not known how active he was outside of the capital during 1955-1963. With the withdrawal of Saloth Sar from Phnom Penh to the Viet-Cambodian frontier in the early 1960s, Ney Sarann was reassigned to work in Mondulkiri. For Lao-Cambodian relations this was an important step, as Ney Sarann married a local lady of Lao ethnicity named Voeun and developed close relations with the local people, be they ethnic Tampuan, Pnong, Kuy, Jarai, Brao or Lao.

The ethnic Lao of Mondulkiri, largely centred on the district of Kaoh Nhek, had important networks with Lao in Stung Treng, Lumphat, Voeunsai, Siempang and of course Laos. Ney Sarann was able to tap into these and rapidly develop the revolutionary movement in the northeast. This was because the ethnic Lao had historically been the most efficient networkers in the region, due to their trade in forest goods and Buddhist missionary activities. Thus allowing them to successfully integrate with the local peoples and gain their trust. During the late 1960s and early 1970s Ney Sarann moved around northeastern Cambodia and Preah Vihear province recruiting people into the KR. In addition, he played an important role as liaison with the Vietnamese and Lao when receiving military supplies down the Sihanouk Trail (note this refers to the northern branch which comes off the Ho Chi Minh Trail in eastern Attapeu province and follows the Xekong valley into Stung Treng province). Khmer Leu and ethnic Lao people from the northeast commented that Ney Sarann’s leadership at the local level was fair and pragmatic, although he was definitely linked to revenge killings of Lon Nol regime figures. In 1973 Ney Sarann received Sihanouk at the Lao-Cambodian frontier with Khieu Samphan and Hou Yuon, after the exiled prince had traveled down the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Ney Sarann and Bou Phat (chief of Preah Vihear province, then known as Sector 103 by the KR) escorted Sihanouk and his Chinese entourage from Veunkham (Lao border crossing point in southern Champasak province) to Phnom Kulen (Siem Reap province) and back.

Before the fall of Phnom Penh, Ney Sarann was moved from the northeast to the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) headquarters in central Cambodia, where it is understood that he took charge of military logistics before the final seizure of the capital. After April 17 Ney Sarann served in Phnom Penh and joined a Democratic Kampuchea (DK) delegation seeking material support from China. The removal of Ney Sarann from northeastern Cambodia in 1973/74 resulted in a breakdown of local support in the KR as new lowland cadres, such as Son Sen’s brother Nikan, enforced CPK policy more strictly on the indigenous community and overtly criticized the Vietnamese as evil parasites. This resulted in groups of Khmer Leu and ethnic Lao, led by figures such as Bou Thong (Tampuan), Seuy Keo (Kachok), Bun Mi (Brao) and Nou Beng (Lao), fleeing to Vietnam and Laos. They later became the new leaders of the People’s Republic of Kampuchea (PRK) due to their privileged status with the Vietnamese, which was cultivated during their time in exile. Bou Thong became Defence Minister in the PRK and Seuy Keo his deputy. Nou Beng became the PRK’s Health Minister, but feel from grace after being caught trafficking opium. Bun Mi was also chosen for high office in the PRK, but he feel chronically ill and insane after receiving bad anesthesia during an operation to remove a bullet from his shoulder.

At this point, early 1976, Angkar Leu reassigned Ney Sarann to the northeast, so as to bring order to the region. In addition, Ney Sarann administered a larger territory which covered Stung Treng, Ratanakiri, Mondulkiri and Kracheh. The embarrassment of the Khmer Leu refugees was complicated by border tensions between Vietnam and Cambodia, which had been simmering since Khmer and Vietnamese forces had snatched island territories from each other in early 1975 and argued over the exploitation of maritime resources. Being an elder brother of the party and fluent in Vietnamese, Ney Sarann was appointed a negotiator in the DK-Socialist Republic of Vietnam border dispute, which extended up into the highland district of O Yadav, Ratanakiri. Around this period, early 1976, suspicions were fermenting inside Angkar Leu as the party leadership felt threatened by ‘hidden rivals’ and Ney Sarann, then commonly known as Ta Ya, became a target of investigation.

It is known that Ya had long-standing differences of opinion with Pol Pot with regards to economic management, but whether he actively conspired against him remains unclear. Certainly he was aligned with CPK moderates such as Koy Thuon (former chief of the KR’s Northern Zone and then DK Economics and Trade Minister) and Hou Yuon, which placed him in dangerous company. Nevertheless it cannot be doubted that Ney Sarann was a party loyalist as he actively pursued the party’s interests in border negotiations. By late 1976 it had been decided by Angkar Leu that Ya was a traitor due to his association with the Vietnamese and other party ‘revisionists’ also accused of plotting to topple the regime. This resulted in his arrest in September and imprisonment at Toul Sleng, where he was questioned and tortured brutally. Subsequently, a large number of cadres from the northeast and elsewhere were purged for being members of Ya’s “Laos Plot” (this term appears in other “confessions” and relates to a revisionist faction in the CPK seeking to adopt a moderate form of socialist construction as employed by the Pathet Lao).

An interesting development from this tragic series of events was that relatives of Ya in Mondulkiri survived the party crackdown and remained faithful to Angkar Leu right up until the 1990s. Ya’s in-laws Laing (secretary of Mondulkiri) and Khamphoun (deputy secretary), who took charge of Sector 105 in the 1970s, died at the hands of each other rather than the guards of S-21 at Toul Sleng prison (A detailed study of their activities by Sara Colm and Sorya Sim is being released soon by the Documentation Centre of Cambodia). Laing’s brothers Lork and Onsi, both ethnic Lao, joined the Sector’s administrative committee in 1978 and in 1986 led hundreds of KR followers from the northeast to the Dangrek Range, where they entered the service of Ta Mok, Son Sen and Ke Pauk. Onsi who served alongside Nhem San (former commander of Division 920 and Son Sen’s killer) now lives in Anlong Veng town, a short distance from Ke Pauk’s children and the S-21 photographer Nhem En, and spends his time gardening like many KR veterans. Mrs. Bua Channa, the niece of Ney Sarann, is now the women’s affairs official for Phum 105, the village where many Khmer Leu associated with the KR leadership are now based. Her husband, Koy Tuan, the former personal assistant to So Sareuan (protégé of Pol Pot and Son Sen’s killer) is also a sub-district official. All of these veterans are firmly settled in Otdar Meanchey province, but maintain their Lao and Khmer Leu culture. Phum 105 sits at the base of the Dangrek escarpment below Pol Pot’s now derelict bunker. It is an unusually tidy village in a picturesque setting, receiving support from a collection of NGOs. This is a sharp contrast to the squalor that surrounds the graves of Pol Pot and Ta Mok, located to the northwest of Phum 105. Some 5-10 kilometers away from the main road linking Anlong Veng with Chong Sa-ngam pass, Phum 105 enjoys a surprising level of harmony in an area where conflict dominated daily life for so long.

6 comments:

ok what is the whole point ?

Not Lao link but lao is used by Vietnam to kill khmer and put the blam on china. We all know that Vietnam controls Lao 90%

nice fear tactic. Extremely effective propaganda for the narrow-minded and uneducated people. Same tactics deploy by Pol Pot. Look where that got him.

Pol Pot is Tai race ??

Very complicated history since Pol Pot knew the tricks of YOUN. Thats why YOUN did all kind of costs to invade their own commie body (Pol Pot).

Youn is very cruels by killing 90% of Khmer than blame on Pol Pot to make Khmer lost trust and believe on Pol Pot.

Khmer Kandal,

SWOT Analyse

win-thai

Stength:

we are stronger because most of military support is from individual's private property-means we are rich no need government budget.

Siams use govt budget to supply army.

Human resources- a lot of Generals-Phd. Excellencies- Co-ministers/Primeministers/ a lot of Kings/Samdachs..Oknhas

Budget: unlimited- collecting from people/monks/poors

Military strength- qualified/ mostly ghost soldiers (invisible)-many Generals

Margic Spell/Black margic: very effective- one thai army died may be due AIDS

Financial resources: land/govt. , any stateowned properties buildings/ heritage natural resources can be sold quickly to buy weapons without any parliamentary Approval ...

Power- handed only one strong man/ every thing can be decided fast...

Political Parties: no need to oppose any govermental decision

Infrastructure-very poor- makes rhais army difficult to move into Cam-territory

Economy: Low- Thais have nothing to eat when invade into Cam....

Weakness:N/A

Oppoertuny- unknown

Treat: uncountable/unknown

Conclusdion- Cam wins Siams unconditionally

Excellency Dr. Bandit Oknha Achar Knoy- Phd. in multi-disciplinary Subjects: Poli/Multi-econom. Laws /From Chea Chamreourn Unviersity PPenh/Campuchia

Post a Comment