New Book on Cambodian History

Dear interested readers:

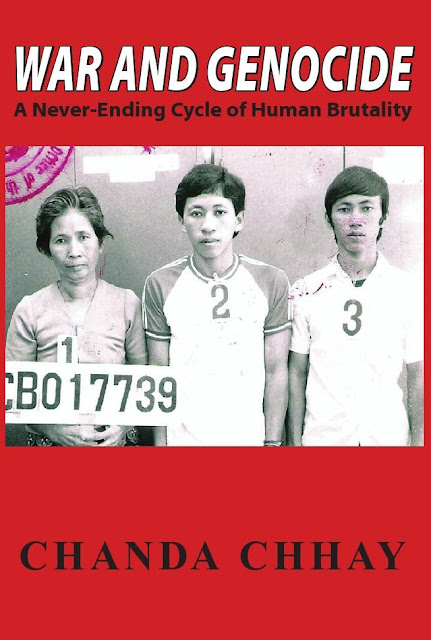

I have just finished publishing a book on recent Cambodian history: WAR AND GENOCIDE: A Never-Ending Cycle of Human Brutality. This book, a memoir, covered the events happened in Cambodia from 1970 to 1989. It deals with the topics of Cambodian Civil War (1970-75), the Khmer Rouge rule (1975-79), life in post Khmer Rouge’s Cambodia (1979-1985) and life in the refugee camps along the Thai-Cambodian border from 1985 to 1989.

This book is being printed by a small print shop in Virginia, and I have not yet contacted any bookstore to distribute them. For those who are interested in obtaining a copy, you can order it on the Internet by going to: http://cambodianchildren.blogspot.com and follow the link by clicking on the cover image of the book. The book would be available for delivery in February 2012. For those of you who have Amazon’s Kindle, iPad, or other electronic book reading devices, you can purchase electronic version of this book on Amazon.com.

I plan to donate a copy of this book to the Cambodian National Library in Phnom Penh, some U.S. Presidential Libraries, Mark Twain Library in Long Beach, and maybe a few other public libraries in the U.S.A. where large community of Cambodians is located. So if you live near one of these libraries mentioned above, you can check it out some time in March or April if your local library received a copy. I do not know how many US Presidential Libraries there are, but if anyone happens to live near one, I would appreciate it if you could send the Library’s address to me via this e-mail: khemara_kakvey@yahoo.com.

Thank you.

Chanda Chhay